Mary Wollstonecraft, PPH and eighteenth century maternal care

November 26th, 2020share this

With all the fuss about the Mary Wollstonecraft statue, it reminded me that one of the topics which was on my mind was the state of maternity care at the end of the eighteenth century. William and Catherine Nicholson seemed to do pretty well with at least 10 kids making it to adulthood. (One infant death is recorded, one of the twelve children still remains a mystery).

Caitlin Moran’s response on Twitter to the statue in Newington Green was ‘If you want to make a naked statue that represents "every woman", in tribute to Wollstonecraft, make it e.g. a naked statue of Wollstonecraft dying, at 38, in childbirth, as so many women did back then - ending her revolutionary work. THAT would make me think, and cry.’{10 November 2020}

So, I turned to Lisetta Lovett, a retired consultant psychiatrist and medical historian, and asked whether this standard of maternal care was normal for the time? Or was Mary Wollstonecraft just particularly unlucky in her medical advisers?

The information which I had compiled on the birth of Mary’s baby with William Godwin was that:

Mary went into labour on Wednesday 30 August, choosing to hire a midwife but no nurse. Godwin described the role of the midwife ‘in the instance of a natural labour, to sit by and wait for the operations of nature, which seldom in these affairs demand the operation of art.’

Little Mary was born at 11.20pm and, sometime after 2.00am, Godwin who was keeping out of the way in the parlour, was informed that the placenta had not been removed. A physician was called for and he removed the placenta ‘in pieces’. The loss of blood was ‘considerable’ and Mary’s health did not improve over the next few days, despite a second doctor visiting and pronouncing that Mary was ‘doing extremely well’.

Godwin wrote that ‘On Monday, Dr Fordyce forbad the child having the breast, and we therefore procured puppies to draw off the milk.’

Then on Wednesday, following a recommendation by family friend Dr Carlisle, ‘it was now decided that the only chance of supporting her through what she had to suffer, was by supplying her rather freely with wine … I neither knew what was too much, nor what was too little. Having begun, I felt compelled under every disadvantage to go on. This lasted for three hours.’

Dr Fordyce was no beginner - see wikipedia - although we do not know if he was the attending doctor on the first two occasions. Dr Carlisle was a close family friend who went on to become the Surgeon Extraordinary to King George IV in 1820.

Lisetta, whose book Casanova's Guide to Medicine: 18th century Medical Practice is due to be published by Pen and Sword Ltd in April 2021, kindly provided the following insights into the medical profession and the little that we know about Mary Wollstonecraft’s death:

The information given here, taken from William Godwin’s diary as well as other sources, raises more questions than it answers. However, it looks like Mary suffered from a post-partum haemorrhage, the cause of which seems to have been a retained placenta.

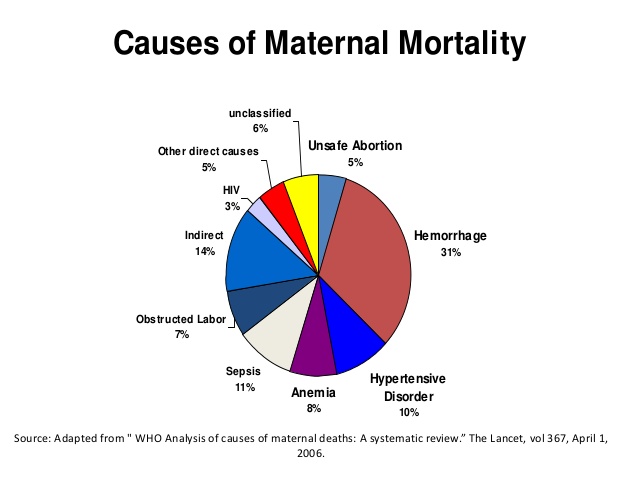

The medical definition of a retained placenta is one that has not been expelled within 30 minutes of delivery. This is still a leading cause of maternal death worldwide, and treatment today is intervention with oxytocin either in the third stage of labour or after delivery and, if this fails, then manual removal under anaesthesia.

By the 19th century, obstetrics had become a medical specialty in its own right, much to the irritation of the midwives. Following the advent of man-midwives, medical doctors moved into the specialty. Neither Dr Fordyce or Dr Carlisle are recorded as having such expertise, but maybe this is not so surprising given that obstetrics as a medical specialty developed a little after their time.

There is a telling quote from a Dr Edgell in On Obstetric Practice, in 1816: "I believe it was an aphorism of the late Dr Clarke, that no woman should die of haemorrhage if an accoucheur is called early...".

Post-partum haemorrhage was a well recognised and potentially lethal complication of child-birth. Accoucheurs applied a variety of treatments to manage it and knew that a quick response could be life-saving. These treatments ranged from a hand in the uterus to stimulate contraction of the uterus and therefore expel the retained placenta (see Davis David in Principles and Practice of Obstetrics 1832-65) to the use of cold water on the stomach, or even injected in the rectum.

The obstetric literature of the early 19th century reveals that there was a lot of medical debate about what measures were most effective, including whether stimulants like brandy or wine should be administered. As the Covid pandemic illustrates, doctors are often in disagreement and so we should not be surprised.

Clearly, Mary would have been better off with an experienced accoucheur, medically trained or not, present throughout the birth ready to respond to any complications. The midwife at least knew that a retained placenta was bad news and informed Godwin who called for a physician. He tried to remove the placenta but probably did not do so completely; a difficult task without the benefit of an anaesthetic and a dreadful ordeal for Mary. For whatever reason, he did not continue to attend her which was a pity.

It is not clear if Mary continued to bleed or not but, given the second doctor's optimism, it sounds as if the bleeding appeared to have stopped.By the time Dr Fordyce is called, it is four days post-partum! He may have suggested the puppies in order to stimulate the uterus to contract and thereby encourage the expulsion of any remaining placenta as suckling induces the body to produce oxytocin. But why not allow the baby to suckle Mary?

Perhaps, she already had a wet nurse, and the doctor wanted to avoid disruption to the baby's feeding. That being said, the cult of breast-feeding your own baby had become popular in the 18th century especially in France where Rousseau’s re-evaluation of maternity was influential. Mary had spent several turbulent years living in France and was no doubt aware of this.

Mary obviously was deteriorating, in part because she continued to lose blood (perhaps internally so it was not obvious) leading to severe anaemia. She may have also developed septicaemia although there is no mention of her having a fever. Ironically, one cause of this could have been manual placental removal. At this time there was little, if no notion, of the importance of keeping one’s hands clean to prevent dissemination of germs.

When Carlisle finally sees her, I think he knows she is going to die and this is why he suggests wine as a 'tonic', not as a treatment but rather as an anaesthetic to make her last hours a little more bearable.

Godwin must have bitterly regretted his early laissez faire comment about childbirth. It is a great pity that he had not employed from the outset an experienced accoucheur, although even so Mary might have died. At this time, childbirth was one of the most dangerous challenges a woman might be obliged to address.

You can follow Lisetta Lovett on her blog Casanova's Medicine.

Today, according to the WHO, about 14 million women around the world suffer from postpartum haemorrhage every year. This severe bleeding after birth is the largest direct cause of maternal deaths. And of course, in addition to the suffering and loss of women’s lives, when women die inchildbirth, their babies also face a much greater risk of dying early. Shockingly, 99% of the deaths from PPH occur in low- and middle-income countries, compared with only 1% in high-income countries.

#35

Carlisle and the Literary Fund save Nicholson from a pauper’s funeral

January 8th, 2020share this

Driving along at lunchtime today, Radio 4 reported on the number of public health funerals being paid for by local authorities at an average cost of £1,403.

Often called a pauper’s funeral, nowadays the local authority will pay for a basic burial when there is no family, or the family cannot afford to pay for funeral arrangements. There have also been stories in the media of people crowdfunding the cost of a funeral.

Neither of these were an option for Catherine Nicholson,when her husband William died at their home in Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury on Monday 21May 1815.

Their eldest son had left home to work in North Yorkshire, for Lord Middleton, but described how ‘My brother remained with him to the last and Carlisle attended him.’

Old friend, and co-discoverer of electrolysis, Anthony Carlisle was at this time the Professor of Anatomy of the Royal Society and in this same year, he was appointed to the Council of the College of Surgeons where for many years he was a curator of their Hunterian Museum.

Nicholson reportedly drank nothing except water since he was twenty years of age, which Carlisle said was the cause of his kidney problems

Despite his sober approach to life and earning well above average for the time, there were also substantial outgoings for ‘a family often or twelve grown up people, adequate servants and a house like a caravansary.’

On the day of Nicholson’s death, Carlisle saw the impoverished circumstances of the family and appealed to John Symmonds at the Literary Fund (now the Royal LiteraryFund) to help:

‘Poor Nicholson the celebrated author, and man of science, died this morning. His family are in the deepest poverty, and I doubt even the credit or the means to bury him.’

I have set a person to apply to the Literary Fund, pray second that application and recommend it to their bounty to be as liberal as their affairs and their rules will permit.’

The next day John Symmonds voted through a grant of £21 for Catherine Nicholson in respect of Nicholson’s talents and industriousness, writing ‘I am extremely desirous that something should be done, most necessarily of that society’ … ‘As he neither prepared for his dispatch, you are written that no time must be lost’.

Once funeral costs were paid, £21 cannot have lasted long, and Catherine Nicholson moved to 11 Grange Street from where she wrote to thank the Literary Fund for ‘the generous respect they were pleased to have for her late husband's abilities’.

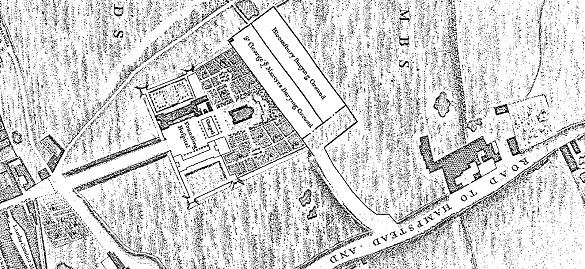

Nicholson was buried on 23 May 1815 in St George’s Gardens, Bloomsbury, one of the first burial grounds to be established at a distance from its church due to the growing problem of overcrowding in London graveyards.

#27

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order