Book Review: Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World

February 9th, 2020share this

At the age of 15, my sons were fairly obsessed with sportand under pressure to work towards impending exams. It is hard to imagine sending them to theother side of the world by sea with the East India Company at that age, as wasthe case with young William Nicholson. It is hard to imagine, the seafaring bustle of the Thames when shipswere built of wood, sails were sewn by hand and sailors could be seen hangingfrom the rigging as he boarded his first Indiaman in 1768.

Nowadays there are daily flights from London to Guangzhou (Cantonto Nicholson) with a journey time of less than ten hours. In 1768, the journeywould take several months and (not being any sort of sailor) it is hard toimagine the life on board – the routines, the food, the highs and lows – that wouldhave been Nicholson’s life.

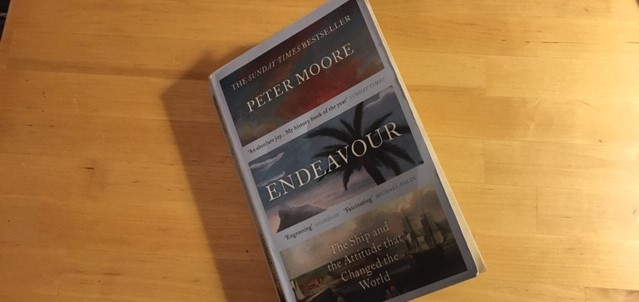

Fortunately, under my Christmas tree this year was a copy ofPeter Moore’s Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World, abook tracing the history of this bark’s life from before it was launched in1764 through its early life in the coal trade between London and the NorthEast, along its famous journey to the South Seas to observe the Transit ofVenus with Captain Cook and Joseph Banks, and finally her role in one of thegreatest invasion fleets in British History.

Moore paints such a vivid picture of the bark and the charactersaboard, the environment in port or at sea, and the political and economicsetting – that it was a very enjoyable read and easy to imagine Nicholsonpassing the Endeavour in the Thames or the Channel as they set sail in the sameyear.

It was charming to meet the young Sir Joseph Banks when hewas full of fun and enthusiasm, eagerly collecting thousands of botanical specimens- for Nicholson’s encounters with Banks two decades later had left me with theimpression of a grand but arrogant and entitled character.

As a young man crossing the equator for the first time, andwithout the means to pay a fine to avoid the experience, Nicholson will havehad to partake in the traditional dunking ceremony which was described in greatdetail when Endeavour crossed in October.

While Cook’s South Sea discoveries have been told manytimes, Moore then traces the history of this vessel further on through a periodof sad neglect into a new role during the revolutionary years as part of the Navalforce which amassed in New York Harbour in 1776.

I was quite carried along by the tale of this doughtyworkhorse, and really enjoyed Moore’s telling of the international political backdrop.

You don’t need to be a historian of sailing to enjoy this historyof an enlightenment hero of the seas.

#28

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

STEM for girls - and how this biography might never have been started

February 3rd, 2017share this

Wedgwood-Museum-in-Barlaston-pic-by-Tom-Pennington-under-creative-commons

One of the questions that I am most frequently asked is how on earth I happened to be writing a book about an eighteenth-century scientist.

Colleagues tend not to be surprised that I am writing a book, as I have always written and published a great deal as part of my career in marketing. But friends and family who have known me since my school days will have witnessed a fundamental aversion to science, particularly biology (too gory) and chemistry (too smelly). I remember my science teacher as being very kind and patient, but cutting open worms and frogs and foul-stinking experiments could never capture my imagination. I hope the S in STEM is more inspiring these days.

On the other hand, history and languages had me in thrall. How could you not want to set sail with the explorers? Or imagine the thrill of inventing the steam engine or designing the first iron bridge and seeing it built? How wonderful to design an intricate piece of pottery and for it to come out of the kiln just as you had planned. I have always maintained an interest in industrial heritage and volunteered with the charity Arts & Business to help two industrial museums in the early 1990s, one of which was the Gladstone Pottery.

Luckily, my very first encounter with Nicholson was in my teens when my grandfather showed me the log book from Nicholson’s voyage to China on the Gatton in 1771. It was like having my own Marco Polo in the family.

This fact was buried deep in the recesses of my mind until around 2009 when I remembered Nicholson and his connection with Josiah Wedgwood, prompted by the Museum winning the Art Fund Prize as Museum of the Year and the financial failure of the Wedgwood business being much in the news. As this was all less than ten miles from my home, it seemed sensible to see if there might be any evidence of Nicholson’s employment by Wedgwood before the collection was dispersed – as was threatened at the time.

Sadly, I could find no employment contract or even payslips – but there was a wealth of correspondence between Nicholson and Josiah Wedgwood or his partner Thomas Bentley in regards to affairs of the agency in Amsterdam. Then later, between 1785 and 1787 Nicholson was secretary to Wedgwood at the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain (about which I will write another day).

I need to confess that it was some time before I learnt of Nicholson’s scientific works, and if my first encounter had been with anything to do with chemistry I would have backed right off.

But finding a direct connection to one of the heroes of marketing (Wedgwood is known as a father of modern marketing) and a major player in the industrial revolution - I was hooked and needed to know more.

#2

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order