'Experiments and Observations Made with Argand’s Patent Lamp,' - Shining a light on Nicholson's concentric wicks

July 18th, 2021share this

In The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin, edited by Desmond King-Hele, Letter 86-6 from Erasmus Darwin to Josiah Wedgwood, 21 April 1786, starts off “Sir, Mr Nicholson is an ingenious and accurate man …” and continues a series of discussions between the men about oil lamp designs, leading to the comment that “The pyramidical lamp would be more pleasing to they eye than the concentric one of Mr Nicholson.”

Having been searching for Nicholson’s 'concentric lamp' for many years, I was delighted to finally track it down in The London Magazine, of May 1785:

Experiments and Observations Made with Argand’s PatentLamp.

Sir

As the attention of the world has been much excited by the powerful effects of Argand’s Lamp, and as there are many who are desirous of making use of it provided its advantages were clearly ascertained, I presume the following description of the instrument and its effects will not be unacceptable to the public.

Yours, &C.

N.

The apparatus consists of two principal parts, a fountain to contain the oil, and the lamp itself. Of the former it is unnecessary to speak: the lamp is constructed as follows. The external parts consist of an upright metallic tube one inch and six-tenths in diameter, and three inches and a half in length, open at both ends. Within and concentric to this is fixed another tube of about one inch in diameter, and nearly of equal length; the space between these two tubes being left clear for the passage of air. The interior tube is closed at the bottom, and contains another similar tube a little more than half an inch in diameter. The third tube is soldered to the bottom of the second. It is perforated throughout so as to admit a current of air to pass through it, and the space between this tube and that which invirons it contains the oil. An ingenious apparatus, containing a piece of cotton cloth whose longitudinal threads are much the thickest, is adapted to nearly fill the space into which the oil flows. It is so contrived that the wick may be raised or depressed at pleasure. When the wick is considerably raised it is seen of a tubular form, and by the situation of the tubes already described is accessible to the air, both by means of the central perforation and the space between the exterior and second tube. When the wick is lighted, the flame is consequently in the form of a hollow cylinder, and is exceedingly brilliant. It is rendered somewhat more bright, and perfectly steady, by adapting a glass chimney whose dimensions are nearly the same with that of the exterior tube first described.

I hope this short description will be sufficient to convey an adequate idea of the instrument and shall therefore proceed to mention its effects. If the central hole be stopped, the flame changes from a cylindrical to a pyramidical form, becomes much less bright, and emits a considerable quantity of smoke. If the whole aperture be entirely or nearly stopped and the combustion becomes still more imperfect. The access of air to the external and internal surfaces of the flame is of so much importance, that a sensible difference is perceived when the hand or any other flat substance is held even at the distance of an inch from the lower aperture. There is a certain length of wick at which the effect of the lamp is the best. If the wick be too much depressed, the flame, though white and brilliant, is short; if it be raised, the flame becomes longer, and consequently the light more intense and vivid. A greater increase of the length, increases the quantity of the light, but at the same time the upper part of the flame assumes a brown hue, and smoke is emitted.

The lamp was filled with oil and weighed, it was then lighted and suffered to burn so as to produce the greatest quantity of light without smoke. After burning one hour and fifty-two minutes, it was extinguished and found to have lost 589 grains of its weight. Now a pint of oil weights 6520 grains and costs sixpence three farthings in retail; the lamp therefore consumes oil to the value of one penny in three hours. It remains to be shewn at what rate per hour the same quantity of light might be obtained from the tallow candles commonly used in families.

The candle called a middling fix, weighing upon an average the sixth part of a pound of avoirdupois, is 10¾ inches long, and 2 inches and 6/10 inch circumference. I have chosen to make my comparison with this candle as being, I imagine, most commonly used. It is to be understood that the lamp gave its maximum light without smoke.

The best method of comparing two lights with each other, that I know of, is this: Place the greater light at a considerable distance from a white paper, the less light may be moved nearer or father from the paper, accordingly as the experiment requires. If now an angular body, as the most convenient figure, be held before the paper it will project two shadows, these two shadows can coincide only in part, and their angular extremities will in all positions but one be at some distance from each other: the shadows being made to coincide in a certain part of their magnitude, they will be bordered with a lighter shadow, occasioned by the exclusion of the light from each of the two luminous bodies respectively. These lighter shadows in fact are spaces of the white paper illuminated by the different luminous bodies, and may with the greatest ease be compared together, because at a certain point they actually touch one another. If the space illuminated by the less light appear brightest, that light is to be removed farther off; and on the contrary, if it be the most obscure, that light must be brought nearer the paper. A considerable degree of precision may be obtained by this method of judging of lights, and by this method the following comparisons were made.

The candle was suffered to burn till it wanted snuffing so much, that large lumps of coaly matter were formed on the upper part of the wick. The candle then at the distance of 24 inches gave a light equal to that of the lamp at the distance of 129 inches: from this experiment it is deduced that the light of the lamp was equal to about 28 candles.

The candle was then snuffed, and it became necessary to remove it to the distance of 67 inches, before its light was so diminished as to equal that of the lamp at the before mentioned distance of 129 inches. From this experiment it is deduced that the light of the lamp was equal to not quitefour candles fresh snuffed.

Another trial with the lamp at the distance of 131 inches and a half, and another candle of the same size at the distance of 55 inches gave the lights equal. The candle was suffered to burn for some time, but did not seem to want snuffing, yet the light of the lamp then appeared to be stronger. The candle when newlysnuffed, the distances remaining the same, appeared rather to have the advantage of the lamp. These numbers give 5 2/3 candles for the light of the lamp, and I imagine the lamp to be rather better than this upon an average, because candles are suffered to go a much longer time without snuffing, and therefore in general give less lightthan was exhibited in these trials.

Another trial with the lamp raised so as to smoke a little, and the candle wanting snuffing, though the form of the wick had not yet begun to change, gave the proportion of the lamp to the candles at about 8 to 1. We may, therefore, I resume, take six middling fixes of tallow candles as an equivalent in light to the lamp. I tried the lamp against 4 candles lighted up together, placed on a distant table with the lamp, I retired till I could just discern the letters of a printed book by the light of the candles, the lamp being covered. I then directed my assistant to intercept the light of the candles and suffer the lamp to shine on the book; the lamp was the brightest. It seemed by trials of this kind to be rather better than five candles; but I was not at that time aware of the difference of the light of tallow candles, accordingly as they have been more or less recently snuffed, and as this method does not appear capable of that degree of exactness and facility the other possesses, I did not pursue it.

From these trials, it is evident that where light beyond a certain quantity is wanted, at a given place, these lamps must be highly advantageous; for the tallow candle being of six in a pound, and burning not quite seven hours, the lamp is equivalent to a pound of these candles lighted up for seven hours. Now, the expence of the lamp for seven hours is less than two pence halfpenny, and that of the candles eight pence; and if the proportion between wax and tallow candles be attended to, it will be seen that the advantages of this lamp for illuminating a theatre are very great.

The wax candles in Covent Garden Theatre are about eighty in number in the sconces, and by estimation may be worth about 2L sterling. An equal quantity of light would be afforded by fourteen of the patent lamps; for the candles used at the theatre do not give quite so much light as a tallow candle of six in a pound. The expence of the fourteen lamps for five hours will not exceed two shillings, according to the foregoing deduction.

Mr. Argand is certainly entitled to all the honour which his talents for philosophical combination have gained; and in the present instance, his claim as an inventor ought not to be disputed, though it should appear that the principle of his lamp was known and even applied to use long ago. Everyone is acquainted with the observation of Dr. Franklin, concerning the increase of light produced by joining the flames of two candles: and double candles have actually been made for, and used by shoemakers from time immemorial. The lamp of many wicks ranged in a right line, and used by watchmakers, gives a very great light for the same reason, namely because the flame being of no considerable thickness has access to air throughout and the combustion is perfectly maintained. Whereas in a thick flame the white heat or perfect ignition extends only to a certain distance from the exterior surface. This is exemplified in a striking manner in those large flames which issue from the chimnies of furnaces. These are luminous only to a certain distance inwards, and the interior part consists of vapour, hot indeed, but not on fire, so that If paper be held in the centre of the flame by means of an iron tube passed through the exterior burning part, the paper will not be set on fire. Mr. Argand has proposed the converting a right lined wick into a circular one; whether this be an advantage or no, except so far as concerns the convenience of having a longer range of conjoined flames within a less space I was desirous of ascertaining. The result of my trials are these.

I took one of Mr. Argand’s wicks, which when cut open longitudinally will form a line at the extremity proposed to be lighted, measuring about two inches and six-tenths. This wick was placed in a brass trough so that the upper edge of the wick was held perpendicular by the straight edge of the trough into which oil was put. The wick was then lighted, and it was easy to raise or lower it above the metallic edge at pleasure, because it adhered by means of the oil to the side of the brass vessel. I thus obtained a flame in a right line equal in length to the periphery of Argand’s flame, and as is the case in that lamp, I found it easy to lengthen or shorten the flame, to cause it to smoke or burn clear as has been before mentioned. The lamp and this right lined flame were placed near each other, and at the same height, the glass chimney being taken off the former: the flames of both were adjusted so as to emit a small quantity of smoke, and their lights tried. The experiment being made by means of the shadows, as before described, their lights proved exactlythe same: but to the eye, looking at both lamps together, the intensity of Argand’s flame appeared considerably the greatest; that is to say, it dazzled more and left a stronger impression when the organ of sight was directed to some other object.

Before I made this experiment I had some expectation, that the long flame would be preferable to the circular one, because I supposed the interior surface of the circular flame, could not throw out so much light as it would have done if it had been developed and exposed. I was even inclined to imagine that the greater part of the light of Argand’s lamp is furnished by the external surface of the flame. But the equality of the lights in the circular and the right-lined flames, shews that this opinion was ill founded, and that flame is in a very high degree transparent.

I therefore directed my attention to the shadow of a lighted candle, and observed, that when the candle does not smoke, the shadow is nearly the same as if the candle were not lighted; that is to say, as if there was no flame. But, if a piece of glass be held up in the same light, it will give a shadow sufficiently sensible: it therefore intercepts more of the light than flame does. This observation accounts for the superior brightness or dazzling of Argand’s lamp. For the light which falls on a given portion of the retina of the eye from Argand’s lamp is much more dense, because it consists not only of the light from the anterior but likewise from the posterior part of the flame.

My ideas on this subject were farther confirmed by an experiment I made with the two lamps; I placed the right-lined flame in such a direction that it should not, as it did before, shine on the paper by its broad side, but in the direction of its length; the comparison of its light with that of Argand’s lamp still exhibited equality. But the long flame was then much more dazzling and bright than that of Argand. This circumstance, which though highly curious, has not, as I know of, been before noticed, at least with that attention it deserves, may be applied to many valuable purposes; one in particular occurs to me that I cannot help mentioning. It should seem that anyproportion of light may be had for microscopic purposes, by means of a long flame placed in the direction of the axis of the illuminating lense.

I tried the transparency of this long flame, placed at right angles, to the ray of Argand’s lamp; it have no shadow; but when its length was placed in the direction of the ray, it gave a shadow bordered by two broad, well defined bright lines, which I have not yet sufficiently examined to be able to give any conjecture respecting them; thought they are undoubtedly owing to some optical deviation of the rays which pass in the vicinity or through the substance of the flame.

These observations on the transparency of flame suggest an improvement of which Argand’s lamp is susceptible. Instead of one ring of flame there may be two, three or more concentric rings, with air passages between them. The inner rings will shine through the outer with more facility than the presentflame does through the glass chimney; and it is probable that the rapidity of the current of air will be increased in a high proportion between these tubes of flame, so as to increase the vehemence and quantity of the ignition, and cause more light to be emitted than would answer to the mere increase of the line of wick.

P.S. Upon looking over this paper it occurred to me, that the singular fact of the same candle that gave only one twenty-eighth part of the light of the lamp, becoming so bright on being snuffed, as to give more than one fourth of the same light it was compared with (which is seven times as bright as before) might seem erroneous or founded in mistake. I have therefore, made several other experiments with snuffed and unsnuffed candles, and am well assured that a candle, newly snuffed, gives in general eight or even nine candles that have been suffered to burn undisturbed for an hour in a still place.

#39

Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture and the feminists’ new clothes

November 15th, 2020share this

I guess I feel that I have a very small right to claim a connection to Mary Wollstonecraft, as my 5 x great grandmother Catherine Nicholson was one of the two close friends (along with Eliza Fenwick) who stayed with and comforted Mary Wollstonecraft in her dying days.

Catherine wrote to William Godwin after his wife’s death to say:

Myself and Mrs Fenwick were the only two female friends that were with Mrs Godwin during her last illness. Mrs Fenwick attended her from the beginning of her confinement with scarcely any interruption. I was with her for the four last days of her life …

She was all kindness and attention & cheerfully complied with everything that was recommended to her by her friends. In many instances she employed her mind with more sagacity upon the subject of her illness than any of the persons about her …

I noticed the fundraising appeal for the statue in 2019 – but it was not clear how much they were trying to raise; how much was still needed; and how it would be spent. There was no information about the finances on the website, only the vague statement “A capital sum for the memorial and a revenue source for the Society will ensure that Wollstonecraft’s legacy and learning will continue.” I was simply seeking to clarify the financial position, but my polite enquiry elicited a rather frosty response, suggesting that I should find another memorial to support.

I’m a fan of figurative sculptures and am lucky enough to live near to the National Memorial Arboretum. As you walk round, you cannot fail to be moved by the way that the sculptures make a historic figure lifeisize (or larger) making more real the boy who represents all those shot at dawn, thechild evacuees, or the ladies Women’s Land Army and Timber Corps. I’d never heard of lumber jills before, but seeing the memorial prompted me to find out more.

So, OK I’ll admit that I’m not very radical in my taste for sculptures, And Mary Wollstonecraft was a radical, so she needs a radical sculpture – right?

Mary Wollstonecraft was strong and adventurous, working as a journalist she headed off to Paris to cover the revolutionary troubles for the publisher Joseph Johnson. But, I’m afraid I cannot see strength and courage in this sculpture.

She was a thinker, an author, and an educator. How is this portrayed in the sculpture? And how is it meant to inspire young women toexpand their minds?

The Mary on the Green website states that “Her presence in a physical form will be an inspiration to local young people in Islington, Haringey and Hackney” … and The Wollstonecraft Society’s objectives are “to promote the recognition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s contribution to equality, diversity and human rights.”

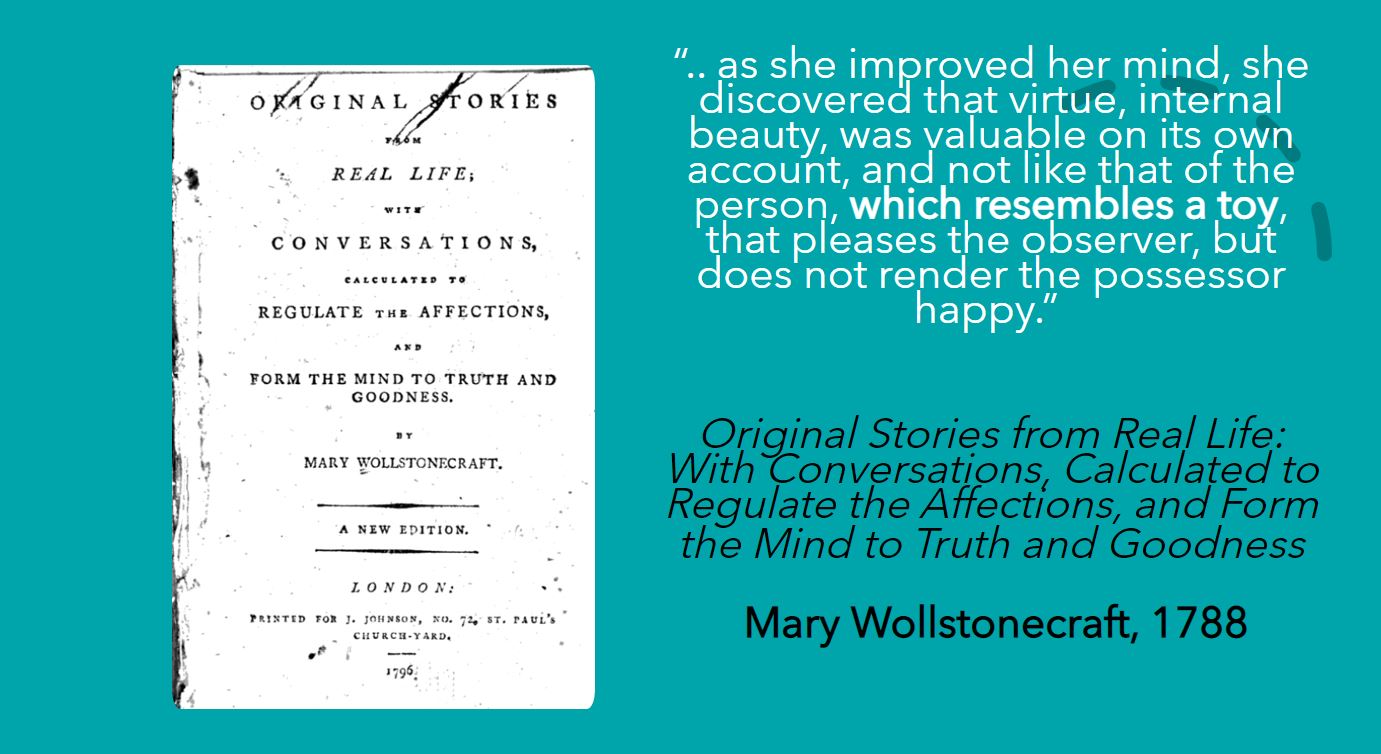

In Original Stories from Real Life: With Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788), Wollstonecarft wrote of a woman who lost her good looks to the small pox and “.. as she improved her mind, she discovered that virtue, internal beauty,was valuable on its own account, and not like that of the person, which resembles a toy, that pleases the observer, but does not render the possessor happy.”

I’m struggling to see how any child who sees this toy-like sculpture will come away with the message that cultivating the mind is more valuable than looks.

On the other hand, (having once accompanied a group of 11-year olds on a school trip to Paris) it is not hard to imagine the giggling and sexist comments that might emerge among some and the embarrassment that might be felt by others.

I don’t envy the teacher who has to create a lesson plan around this educational trip!

#34

Termites tuck into Nicholson’s Journals in Bombay in 1859

August 9th, 2020share this

Here is an extract from the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, from Monday 28th November 1859 telling of a sad fate for Nicholson’s Journal.

“It is with much regret that the Committee have to inform the Society that the White Ants, which infect the Town Hall throughout, have found their way into the Library, and destroyed many of the books.

This was first discovered in September 1858, and since that there have been several incursions … during which 12 works or 33 volumes have been destroyed, and 12 works or 38 volumes slightly injured; fortunately those which have been destroyed have chiefly consisted of Novels, the others have been works in the classes of Classics and Chemistry; - “Nicholson’s Journal” however, has severely suffered.”

#30

Solving the C18th puzzle of scientific publishing

July 13th, 2020share this

A guest blog, by Anna Gielas, PhD

William Nicholson made Europe puzzle. Continental men of science translated and reprinted articles from his Journal on Natural Philosophy,Chemistry and the Arts on a regular basis—including the mathematical puzzles that Nicholson published in his column ‘Mathematical Correspondence’.

When Nicholson commenced his editorship in 1797, his periodical was one of numerous European journals dedicated to natural philosophy. Nicholson was continuing a trend that had existed on the continent for over a quarter of century. But at the same time, Nicholson was committing to a novel form of philosophical communication in Britain. The British periodicals dealing with philosophy and natural history were linked with learned societies. Besides the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, numerous philosophical societies in other British towns, including Manchester, Bath and Edinburgh, published their own periodicals. The London-based Linnaean Society, which had close ties to the Royal Society, also printed its transactions.

Nicholson’s editorship did not have any societal backing. He did not conduct his periodical in a group, but by himself. These circumstances made his Journal something different and novel—maybe even revolutionary. In the Preface to his first issue, Nicholson confronted the very limited circulation of society and academy-based transactions and their availability to the ‘extreme few who are so fortunate’. He made it his editorial priority to reprint philosophical observations from transactions and memoirs—to make them accessible to a wider audience.

Considering his friendship with the radical dramatist Thomas Holcroft and his collaboration with the political author William Godwin, we can think of Nicholson’s editorial priority in political terms: he wished to democratize philosophical communication. Personal experiences could have played a role here, too. Nicholson appears to have initially harbored some admiration for the Royal Society and its gentlemanly members. But he did not become a Fellow due to his social background. Whether he considered his inability to be part of the Society a social injustice is not clear. But this experience likely played a role in his decision to edit and reprint from society transactions.

There seems to be a political dimension to Nicholson’s editorship—yet the sources available today do not allow any straight-forward reading of the motives for his editorship. He did not present his editorship as a political move. Instead, he used the rhetoric of his contemporaries—the rhetoric of utility: ‘The leading character on which the selections of objects will be grounded is utility’, he wrote in his Preface. The Journal was supposed to be useful to ‘Philosophers and the Public’.

Nicholson had acquired the skills necessary for editing a periodical over many years. It seems that his organizing role in a number of societies and associations was particularly helpful to hone such abilities—for example, his membership at the Chapter Coffee House philosophical society. In mid-November 1784, Nicholson and the mineralogist William Babington were elected ‘first’ and ‘second’ secretaries of the society. During the gathering following his election, Nicholson appears to have raised 13 procedural matters for discussion and action. According to Trevor Levere and Gerard Turner, Nicholson ultimately ‘made the meetings much more effective and disciplined’.

His organizing role brought and kept him in touch with most of the Chapter Coffee House society members which enabled him to expand and affirm his own social circle among philosophers. So much so, that some of the society members would go on to contribute repeatedly to Nicholson’s Journal. As the ‘first’ secretary, Nicholson gained experience in steering a group of philosophers and experimenters towards a productive and lasting exchange—a task similar to editorship.

Nicholson was skilled in fostering and maintaining the infrastructure of philosophical exchange. His contemporaries were well aware of it and sought his support on a number of occasions. Among them was the publisher John Sewell who invited Nicholson to become a member of his Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Here, Nicholson and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and Vice-President of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, had one of two conflicts.

Philosophical societies in late eighteenth-century London tended to have presidents and vice-presidents, committees and hierarchies. More often than not, these hierarchies mirrored the members' actual social ranks. As an editor, outside of a society, Nicholson was free from hierarchies. He could initiate and organize philosophical exchange as he saw fit—which likely made editorship attractive to him.

For Nicholson who was almost constantly in financial difficulties, editing was also a potential source of additional income. After all, the same month the first issue of his Journal came out, Nicholson's tenth child, Charlotte, was born. But the Journal did not become a commercial success. Yet, he continued it over years, until his health deteriorated. Non-material motives seem to have outweighed his monetary needs.

His journal was an integral part of Nicholson’s later life—particularly when he no longer merely reprinted pieces from exclusive transactions. After roughly three years since the first issue appeared, his Journal began to turn into a forum of lively philosophical discourse. In the issue from August 1806, for example, he informed his contributors and readers of the ‘great accession of Original Correspondence’, which he—whether for the reason of ‘utility’ or democratizing philosophy—published in later issues rather than foregoing publication of any of them.

Outside of Britain, the Journal was read in the German-speaking lands, Russia, Netherlands, Scandinavia, France and others. Nicholson made Europe puzzle indeed. He united geographically as well as culturally and socially distant individuals, bringing European men-of-science closer together.

Further reading:

Anna Gielas: Turning tradition into an instrument of research: The editorship of William Nicholson (1753–1815),

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1600-0498.12283

#29

Summer reading: Special offer for members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association

September 30th, 2018share this

The following article was first published in the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association newsletter on 15 August 2018.

‘I used to write a page or two perhaps in half a year, and I remember laughing heartily at the celebrated experimentalist Nicholson who told me that in twenty years he had written as much as would make three hundred Octavo volumes.’

William Hazlitt, 1821

This year has seen numerous celebrations of Mary Shelley’s ‘foundational work in science fiction’, but where did Mary Shelley learn about electricity?

Historians often trace this knowledge to a copy of Humphry Davy’s Elements of Chemical Philosophy which was published in 1816 – but many years before this, the child Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin had access to scientific instruments at 10 Soho Square with her playmates – the five daughters of William Nicholson (1753-1815).

The scientist and publisher William Nicholson was one of her father’s closest friends. In his diary, William Godwin records more than 500 meetings with Nicholson and his family between November 1788 and February 1810. Aside from their mutual friend the dramatist Thomas Holcroft (1,435 mentions) and direct family members, only a handful of other acquaintances are mentioned more frequently in Godwin’s diary.

Nicholson had opened a Scientific and Classical School at his home in Soho Square in 1800. It was here in the Spring that, with Anthony Carlisle, he famously decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen using the process now called electrolysis.

Electrical experiments had long been an interest of Nicholson who had two papers on the subject read to the Royal Society by Sir Joseph Banks in 1788 and 1789.

In those days, science - or natural philosophy as it was called - was also a leisure activity. Scientific instruments were the latest toys for the affluent and experiments provided entertainment. One after-dinner game was The Electric Kiss: where young men would attempt to kiss a young lady who had been charged with a high level of static electricity. Sadly, the kisses were rarely obtained as, on approaching the young lady, the men would be jolted away by an electric shock.

In a house full of several children, and a dozen energetic students, Mary witnessed and is likely to have participated in experiments and pranks with the air pump or Nicholson’s revolving doubler – his invention of 1788 with which you could create a continuous electrical charge.

Despite his circle of literary friends, Nicholson is better known among historians of science for A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts which ran between 1797 and 1813 and was the first monthly scientific journal in Britain. It revolutionised the speed at which scientific information could spread - in the same way that social media has done more recently - and the Godwin family no doubt received copies.

Full sets of Nicholson’s Journal, as it was commonly known, are rare. Certain editions are particularly sought after, such as those which include George Cayley’s three papers on the invention of the aeroplane.

But Nicholson’s first success as an author was fifteen years previously with his Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782. This was the same year that he wrote the prelude to Holcroft’s play Duplicity.

Nicholson quickly abandoned writing for the theatre, but he never abandoned his literary friends with their anti-establishment views, and his body of work is more extensive than the voluminous scientific translations and chemical dictionaries for which he is best known – some of which change hands for thousands of pounds.

Other works included a six-day walking tour of London, a book on navigation – based on Nicholson’s experiences as a young man with the East India Company – and translations of the exotic biographies of the Indian Sultan Hyder Ali Khan and the Hungarianadventurer Count Maurice de Benyowsky. Nicholson also contributed short biographies for John Aikin’s General Biography series; he launched The General Review which ran for just six months in 1806; and heproduced a six-part encyclopedia.

Before Nicholson came to London, he had spent a period working for the potter Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam. Wedgwood held young Nicholson in high regard, commenting in 1777 that ‘I have not the least doubt of Mr Nicholson's integrity and honour’. Then in 1785, when Wedgwood was Chairman of the recently established General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he appointed Nicholson as secretary. In this role, Nicholson produced several papers on commercial issues including on the proposed IrishTreaty and on laws relating to the production and export of wool.

Towards the end of his life, Nicholson put his technical knowledge to work as a patent agent and later as a civil engineer, consulting on water supply projects in West London and Portsmouth. The latter project faced stiff competition from another local water company and, in 1810, Nicholson published A Letter to the Incorporated Company of Proprietors of the Portsea-Island Water-Works.

As William Hazlitt indicated, in the opening quotation, Nicholson’s works were extensive. His activities were varied and there is much in his writings that will be of interest to historians of literature, commerce and inventions, as well as to historians of science and the Enlightenment.

A full list of Nicholson’s publications can be found in The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son, which was first published by Peter Owen Publishers earlier this year (£13.99). The original manuscript, written 150 years ago in 1868, is held at the Bodleian Library.

Free postage and packing is offered to members of the ABA when purchasing direct from www.PeterOwen.com. Simply use the Coupon code ‘1753-1815’ in the shopping cart before proceeding to checkout.

#25

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

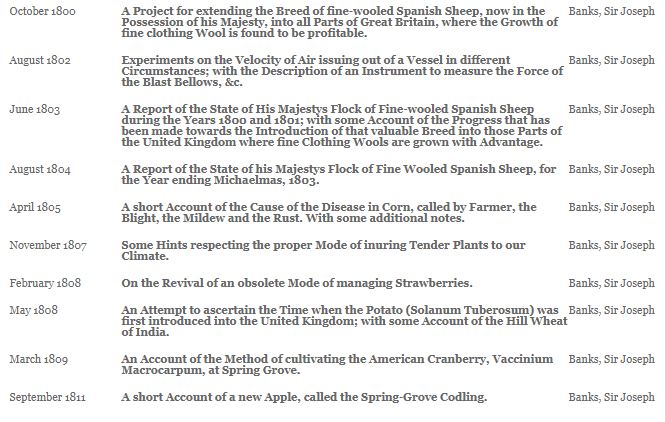

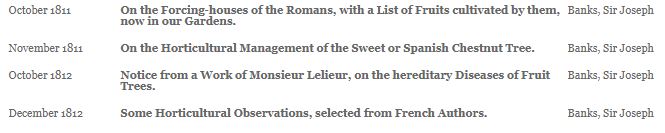

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

Holcroft, Nicholson and the C18th gig economy

September 3rd, 2017share this

While the phrase ‘gig economy’ has been all over the mainstream media recently with the publication of the Good Work: The Taylor Review of modern working practices, the expression has been around for nearly a decade and insecure working arrangements have been around for centuries. In 2015, The Financial Times chose the expression for its FT 2015 Year in a Word, by Leslie Hook.

Leslie traced the expression back to the height of the financial crisis in 2009, ‘when the unemployed made a living by gigging, or working several part-time jobs, wherever they could’ with the word ‘gig’ emanating from jazz club musicians in the 1920s.

I could not help noting the similarities with life for many in the 18th Century as I re-read the Memoirs of the Late Thomas Holcroft by William Hazlitt. Holcroft was a good friend of Nicholson, and his early employment history included time as a shoemaker, a stable lad at Newmarket, and as a chorister where he earned the nickname ‘the sweet singer of Israel’.

Holcroft headed for London where, like many young people today, he ‘felt the effects of poverty very severely’ and ruminated on what might have resulted from a good education. He was getting so desperate for work that he was heading to the office which recruited soldiers for the East India Company when he bumped into a friend who mentioned an opportunity with a travelling theatre company in Dublin. Then, for several years, he traipsed about the country in search of one opportunity after another before finally settling in London as a writer and dramatist.

Nicholson too was no stranger to the gig economy, having first worked for Josiah Wedgwood on a 'consultancy assignment' to Amsterdam to investigate financial irregularities with the Dutch sales agency. This had led to an employed position in Amsterdam, but only for a discrete project and so Nicholson had to return to London in search of work.

When young William Nicholson came to lodge with Holcroft at Southampton Buildings in around 1780, Holcroft subcontracted bits of writing to him. He also tried to persuade Nicholson that ‘at least as much revenue could be obtained from literary publications, as from any of the objects … of his thoughts.’

Over 25 years, Nicholson successfully built a steady income from writing, translating and publishing. But, with a large family to feed, he also took several gigs on the side. Projects included consulting on technical issues, sometimes as an early patent agent, acting as Secretary to the Chapter Coffee House Society and the General Chamber of Manufacturers. Then in the mid-1800s, he took on assignments as a civil engineer for a couple of water supply projects.

Unfortunately, like many who operate in the gig economy today, Holcroft and Nicholson did not set aside enough of their incomes during the good times to provide for ill-health in their old age.

The gig economy is not such a new phenomenon, but it does remind us that workers did not always enjoy the social safety nets that we often take for granted and are comparatively recent developments in the history of employment:

•1908 – old age pension introduced for men over 70

•1938 – paid holiday introduced

•1940 – old age pensions introduced for women

•1948 - the NHS was introduced.

#12

World Helicopter Day – On Aerial Navigation

August 20th, 2017share this

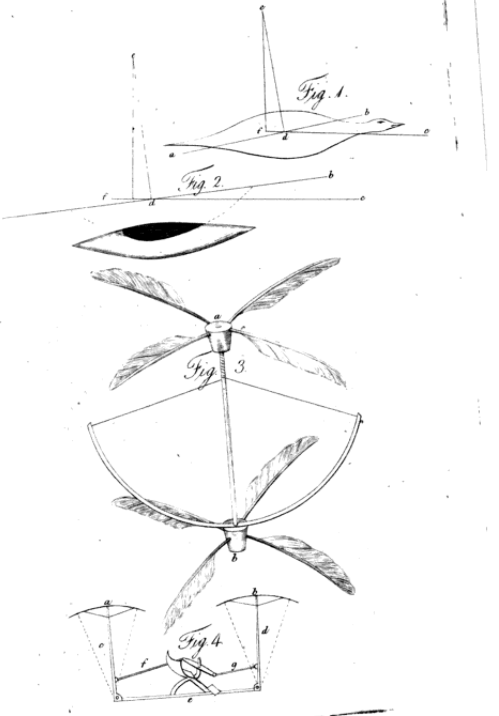

I have just noticed that 20 August is World Helicopter Day, and on a recent visit to the helicopter museum in Weston-Super-Mare (the World's Largest Dedicated Helicopter Museum) with my father, a former helicopter engineer, I spotted a reference to the three papers by Sir George Cayley in Nicholson’s Journal.

‘On Aerial Navigation’ was published in three parts:

Nicholson’s Journal, November 1809

Nicholson’s Journal, February and March 1810

I have since seen this described online, by Mississippi State University, as:

"Arguably the most important paper in the invention of the airplane is a triple paper On Aerial Navigation by Sir George Cayley. The article appeared in three issues of Nicholson's Journal. In this paper, Cayley argues against the ornithopter model and outlines a fixed-wing aircraft that incorporates a separate system for propulsion and a tail to assist in the control of the airplane. Both ideas were crucial breakthroughs necessary to break out of the ornithopter tradition."

This sketch from the November 1809 paper.

If any historians of aeronautic developments would like tocontribute a guest blog on the significance of Cayley’s papers, please email us at

info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#12

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order