In good society … (updated)

October 10th, 2024share this

Image: A Mad Dog in a Coffee House by Thomas Rowlands, 1809 - Source wikimedia

If I have a bit of spare time on a business trip to London, then I can often be found in the Royal Society ploughing through the minute books to see whether William Nicholson was ever proposed as a member.

Nicholson’s son, also called William, recalled that:

The main point on which my father felt aggrieved was his rejection at the Royal Society. My father had been recommended by several of the members of the Society to offer himself. He was duly proposed, but objected to.

It came to my father’s ears that Sir Joseph Banks was the chief objector, having said that whatever pretensions Mr Nicholson had to the membership, he did not think a ‘sailor boy’ a fit person to rank among the gentlemen members of the Royal Society, or words to that effect.

But, let us not dwell on his one disappointment, when Nicholson enjoyed such a wide variety of acquaintances through his membership of a number of societies, each of which I will return to in a future blog:

The Cannonians (around 1780) – this was the name of an informal dining club that met in a cookshop in Porridge Island near St. Martin's-in-the-Fields.

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787) – which had no official name, but was often called the Chapter Coffee House Society, after its main meeting place. See this blog for details of the membership. William Nicholson joined in 1783, proposed by Jean-Hyacynthe de Magellan and John Whitehurst, and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain and Ireland (1785-1787) – Josiah Wedgwood was the first chairman and proposed Nicholson as secretary.

The Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (1791-1796) – established by Mr John Sewell, a publisher and friend of Nicholson who proposed him as a member from outset.

The Royal Institution, Committee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis (June 1801- ) Nicholson was appointed to this committee with Anthony Carlise, presumably proposed by Humphry Davy.

Literary and Philosophical Society (Newcastle-upon-Tyne) - Nicholson was an honorary member in 1801 - https://tinyurl.com/y9ads692

The Geological Society of London (1807-) Nicholson joined as a member in 1812, proposed by Anthony Carlisle, James Parkinson, Arthur Aikin (a founder of the society) and Richard Knight.

Publications of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (April 1791 to May 1794)

February 20th, 2022share this

I thought this might be a useful place to list all the publications which I had come across for the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (April 1791 to May 1794):

An Address to the Public,from the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Instituted 14thApril 1791.

Some Account of the Institution, Plan, and Present State, of the Societyfor the Improvement of Naval Architecture. September 1792

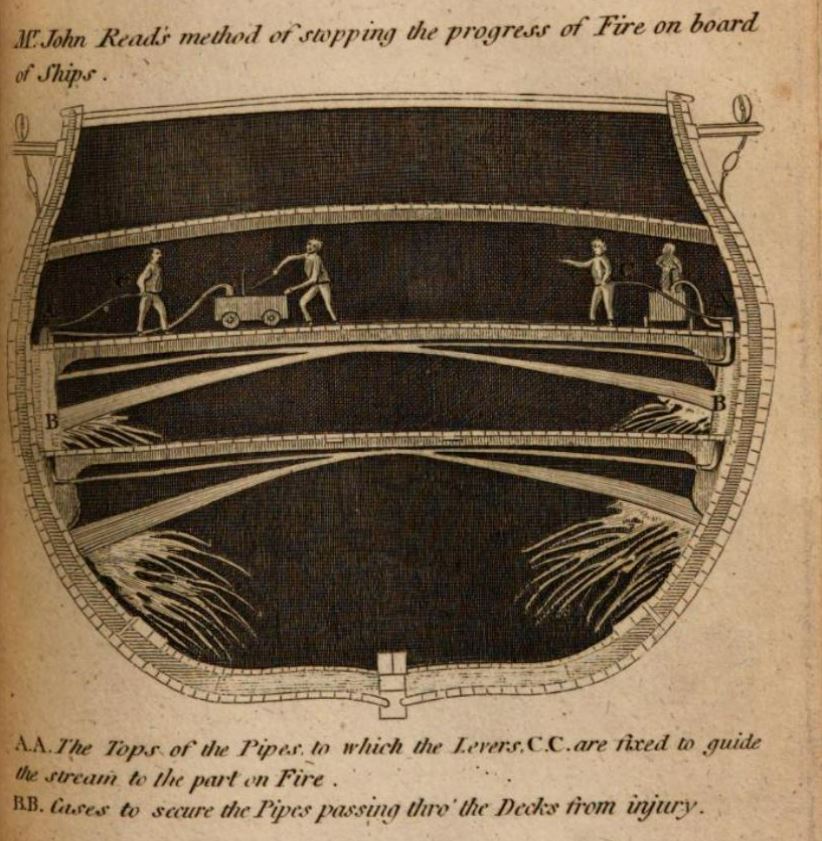

Premiums offered by theSociety ... and a list of the committee ... To which is annexed, an account ofMr. J. Read's method of stopping the progress of fire on board of ships. January 1793

The Report of the Committee Appointed to Manage the Experiments of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, January 1794

A Treatise concerning theTrue Method of finding the Proper Area of the Sails for Ships of the Line, andfrom thence the length of masts and yards. (Supplement, taken from the"New Transactions of the Swedish Academy of Sciences" ... concerninga true method for finding the height of the centre of gravity in a ship, etc.) ByF. H. af Chapman. Translated from the Swedish. With diagrams. January 1794

#40

Book Review: Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World

February 9th, 2020share this

At the age of 15, my sons were fairly obsessed with sportand under pressure to work towards impending exams. It is hard to imagine sending them to theother side of the world by sea with the East India Company at that age, as wasthe case with young William Nicholson. It is hard to imagine, the seafaring bustle of the Thames when shipswere built of wood, sails were sewn by hand and sailors could be seen hangingfrom the rigging as he boarded his first Indiaman in 1768.

Nowadays there are daily flights from London to Guangzhou (Cantonto Nicholson) with a journey time of less than ten hours. In 1768, the journeywould take several months and (not being any sort of sailor) it is hard toimagine the life on board – the routines, the food, the highs and lows – that wouldhave been Nicholson’s life.

Fortunately, under my Christmas tree this year was a copy ofPeter Moore’s Endeavour – The Ship and the Attitude that Changed the World, abook tracing the history of this bark’s life from before it was launched in1764 through its early life in the coal trade between London and the NorthEast, along its famous journey to the South Seas to observe the Transit ofVenus with Captain Cook and Joseph Banks, and finally her role in one of thegreatest invasion fleets in British History.

Moore paints such a vivid picture of the bark and the charactersaboard, the environment in port or at sea, and the political and economicsetting – that it was a very enjoyable read and easy to imagine Nicholsonpassing the Endeavour in the Thames or the Channel as they set sail in the sameyear.

It was charming to meet the young Sir Joseph Banks when hewas full of fun and enthusiasm, eagerly collecting thousands of botanical specimens- for Nicholson’s encounters with Banks two decades later had left me with theimpression of a grand but arrogant and entitled character.

As a young man crossing the equator for the first time, andwithout the means to pay a fine to avoid the experience, Nicholson will havehad to partake in the traditional dunking ceremony which was described in greatdetail when Endeavour crossed in October.

While Cook’s South Sea discoveries have been told manytimes, Moore then traces the history of this vessel further on through a periodof sad neglect into a new role during the revolutionary years as part of the Navalforce which amassed in New York Harbour in 1776.

I was quite carried along by the tale of this doughtyworkhorse, and really enjoyed Moore’s telling of the international political backdrop.

You don’t need to be a historian of sailing to enjoy this historyof an enlightenment hero of the seas.

#28

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

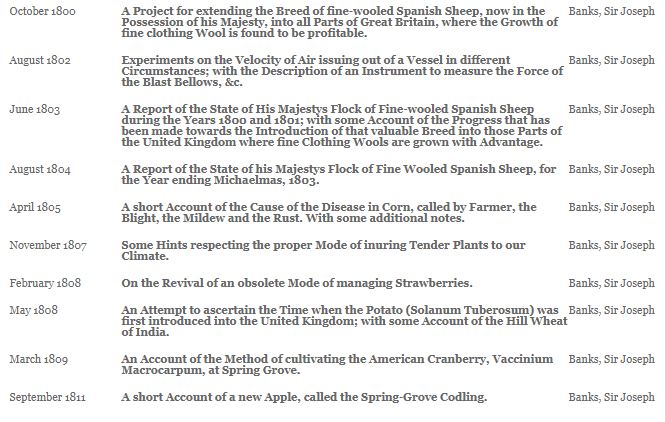

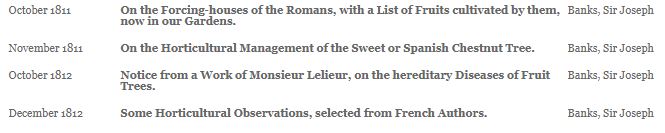

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

2017 Hull & 1804 a 'Half-mad' story of South Sea Whaling

May 1st, 2017share this

Image: Robert Salmon [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The second interesting discovery via the Hull Maritime Museum was sparked by their display of the history of whaling. Although the whalers departing from Hull headed mainly for the Arctic Waters, there was some mention of the south sea fisheries, and I was pointed towards a most useful resource: the British Southern Whale Fishery (BSWF) Database.

Run by the University of Hull, the online database supplies details of actual voyages, and the people involved in the BSWF between 1775 and 1859.

The British southern whale fishery, commenced in 1775 and its trade was almost exclusively carried out from London. Initially it focused primarily in the mid to south Atlantic; by the mid-1790s it had moved to the Pacific and Indian Oceans and was limited to the areas off the coasts of Africa, South America and the east coast of Australia, but by 1815 the trade had spread to the wider Pacific.

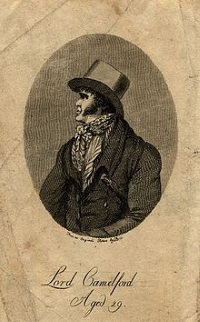

The trade was often referred to as the South Seas Whale Fishery, and it was some unfortunate project related to this with Thomas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, (the Half-Mad Lord) which was at the root of Nicholson’s financial problems in later life.

Camelford’s project involved an investment in two whaling ships, believed to be called the Experiment and the Wilding which were secured by a ‘reputable merchant’ called Mr Rogers.

The Wilding is listed on the database; it sailed in 1803 and returned in 1805 under the command of John Borlinder.

Unfortunately, there are a number of vessels called the Experiment, but none of these sailed in the southern seas around 1804, the year in which Camelford was shot in a duel and died.

If you can contribute any information on the Experiment or the Wilding, Mr Rogers or John Borlinder, or their connection with homas Pitt, Baron Camelford II, please get it touch: info@nicholsonsjournal.com.

#7

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order