In good society … (updated)

October 10th, 2024share this

Image: A Mad Dog in a Coffee House by Thomas Rowlands, 1809 - Source wikimedia

If I have a bit of spare time on a business trip to London, then I can often be found in the Royal Society ploughing through the minute books to see whether William Nicholson was ever proposed as a member.

Nicholson’s son, also called William, recalled that:

The main point on which my father felt aggrieved was his rejection at the Royal Society. My father had been recommended by several of the members of the Society to offer himself. He was duly proposed, but objected to.

It came to my father’s ears that Sir Joseph Banks was the chief objector, having said that whatever pretensions Mr Nicholson had to the membership, he did not think a ‘sailor boy’ a fit person to rank among the gentlemen members of the Royal Society, or words to that effect.

But, let us not dwell on his one disappointment, when Nicholson enjoyed such a wide variety of acquaintances through his membership of a number of societies, each of which I will return to in a future blog:

The Cannonians (around 1780) – this was the name of an informal dining club that met in a cookshop in Porridge Island near St. Martin's-in-the-Fields.

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787) – which had no official name, but was often called the Chapter Coffee House Society, after its main meeting place. See this blog for details of the membership. William Nicholson joined in 1783, proposed by Jean-Hyacynthe de Magellan and John Whitehurst, and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain and Ireland (1785-1787) – Josiah Wedgwood was the first chairman and proposed Nicholson as secretary.

The Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (1791-1796) – established by Mr John Sewell, a publisher and friend of Nicholson who proposed him as a member from outset.

The Royal Institution, Committee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis (June 1801- ) Nicholson was appointed to this committee with Anthony Carlise, presumably proposed by Humphry Davy.

Literary and Philosophical Society (Newcastle-upon-Tyne) - Nicholson was an honorary member in 1801 - https://tinyurl.com/y9ads692

The Geological Society of London (1807-) Nicholson joined as a member in 1812, proposed by Anthony Carlisle, James Parkinson, Arthur Aikin (a founder of the society) and Richard Knight.

Publications of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (April 1791 to May 1794)

February 20th, 2022share this

I thought this might be a useful place to list all the publications which I had come across for the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture (April 1791 to May 1794):

An Address to the Public,from the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Instituted 14thApril 1791.

Some Account of the Institution, Plan, and Present State, of the Societyfor the Improvement of Naval Architecture. September 1792

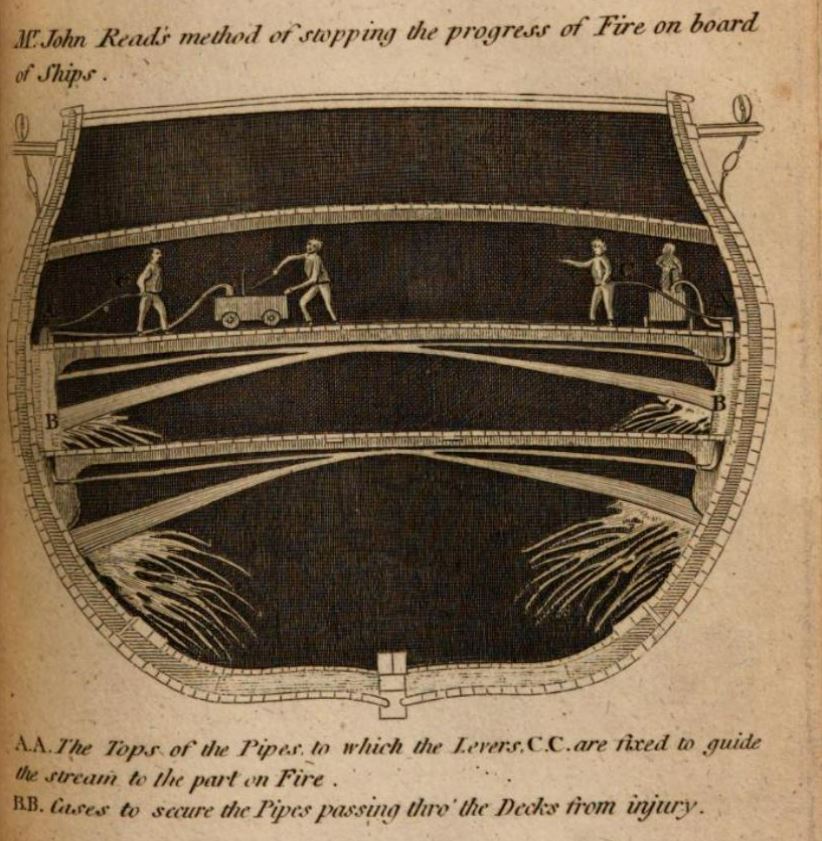

Premiums offered by theSociety ... and a list of the committee ... To which is annexed, an account ofMr. J. Read's method of stopping the progress of fire on board of ships. January 1793

The Report of the Committee Appointed to Manage the Experiments of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, January 1794

A Treatise concerning theTrue Method of finding the Proper Area of the Sails for Ships of the Line, andfrom thence the length of masts and yards. (Supplement, taken from the"New Transactions of the Swedish Academy of Sciences" ... concerninga true method for finding the height of the centre of gravity in a ship, etc.) ByF. H. af Chapman. Translated from the Swedish. With diagrams. January 1794

#40

A long shot … will our Bloomsbury Festival live event survive the 'Covid-19 circuit-break'?

October 12th, 2020share this

A short history of the ups and downs of organising a live event for the Bloomsbury Festival during the coronavirus

On 17 March 2020, just a few days before our world turned upside down due to the coronavirus, I received an email from Diana at the Friends of St George’s Gardens (where Nicholson is buried):

“This is just a long shot. But how would you like to do a walk round St George’s Gardens and talk about William Nicholson in late October, as part of the Bloomsbury Festival? We did this in 2018 for Zachary Macaulay with two actors in costume – Zachary and his wife. … “

A few days later on 23 March, the nationwide lockdown was announced by the government. The prospect of 12 weeks at home provided the perfect opportunity to write up a script, and with everything looking so bleak, this was something exciting to look forward to.

At that time, although all summer events were being cancelled, we all thought that life would be back to normal after a few months and October was far enough ahead to be safe. How incredibly naïve!

By the end of April, we’d all embraced the powers of Zoom and a meeting with the Bloomsbury Festival team, led by Rosemary Richards, explained that they were going ahead with various contingency plans, and we should plan an online version as a backup.

I was also interested to see that UCL were participating in the festival – for I knew they had a history of science faculty. As I had started writing the script and reached the scientific bits, I was wondering how we could get the discovery of electrolysis across in an interesting and engaging way – as this was distinctlynot my area of expertise.

Having seen that the festival team had been involved with the science festival GravityFest, I asked if they might have any useful contacts at UCL. Fortunately on they wrote to say “UCell are happy to help/collaborate with you in giving a talk at the Bloomsbury festival” and Alice, Harry and Keenan agreed to comealong and recreate the water-splitting experiment from May 1800 and then demonstrate how electrolysis plays a role in clean energy production with their hydrogen fuel cell.

In May Diana emailed to mention “another committee member, Ian Brown, who is a theatre director and will have good ideas about how to make the most of a story.” Looking him up online to find he had run the highly regarded West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds for a decade, I didn’t know whetherto be delighted or petrified. The sum total of my dramatic experiences to date comprised playing Mary in a nativity play at infant school and a mime on a student trip to Santander a few decades ago – neither role having had any script – what had I let myself in for?

Thankfully, Ian turned out to be delightful and thoroughly put me at ease. He suggested the performance should take the form of an interview with Nicholson’s ghost (great idea!) and was also very pragmatic about the format of the online version when my multi-media ambitions ran away with themselves. Ian also took on the role of finding an actor, when it turned out that my friend was in a high-risk group and was shielding could be confined indefinitely (as it seemed at the time).

Details of the event had to be finalised for the programme by the end of May, and so it was agreed to perform live on the first Saturday 17th and the online event was scheduled for Tuesday 20th October. The title of the talk was agreed as “In conversation with Mr Nicholson” referring to the conversazione evenings which were hosted by Georgians.

The running order started with me interviewing the ghost of Nicholson about his life up to the point of the experiment in 1800 – then we would introduce the UCell team and Nicholson would take up the baton and ask them about their experiments and the future usefulness of his work. I was thrilled that we would be able to show how relevant his work had been to the future of clean energy, and in a way that would be much more visually interesting for an audience.

However, this was not without a few challenges of its own, as the UCell team had to get approval from the university for their participation and use of the fuel cell stack (a very valuable piece of kit, the size of a large supermarket trolley). And while we could record the interview on zoom at any time for use in the online version, the only chance to video the experiments would be on the 17th October (Covid-19 permitting).

We all pressed on in good faith, and I booked the last week of May off work to get the script finalised and over to Ian.

On 18 June, the festival team emailed to say “As you know, we are working with the current, and ever-changing, government advice regarding Covid-19 and social distancing, and of course the safety of our performers and festival goers is our absolute priority. With this in mind, we have come to the decision to cap the number of participants for your talk to 20 participants for the time being. As you can imagine, this is to protect the safety of the people attending, and yourself. If nearer the time restrictions are relaxed, we will release more tickets.” Having scoped out the layout in the gardens the FoSGG team were later able to increase this to a maximum of 30.

At the beginning of July, Ian helped me to shape the script – adding more depth to the character of Nicholson and his family, explaining all the other characters, adding some gossip and eliminating non-sequiturs!

We still didn’t have an actor for Mr Nicholson. Hugh Jackman was of course isolating in Australia, so I spent an evening looking through actor directory websites – mercilessly judging men solely on their appearances.

Meanwhile, lockdown had not ended, and we were all still working at home. It was necessary to decide on whether to charge participants an entry fee, and in the end it was decided that it was “a bit more than a talk, with a scientific demo and a speaker in costume” so fees were set at £8 for the live event and £5 for the online event. The Bloomsbury Festival typically do a 50/50 split with paid ticketed events, and they have a “box office intern” and volunteer present to deal with last minute onsite tickets and to take payments. Soon, the contract was signed and Diana was looking into whether we should or could use microphones.

On 21 July, Ian emailed to say he had found a potential Mr Nicholson “I got an email from a local actor this morning - he’s a barrister as well as an actor. Going to meet him.” A week later Julian Date had joined the team – a family barrister by day, I was amazed that he would have the head space to learn so many lines as well as running court cases up to the performance, but apparently these use different parts of the brain.

August and September saw us all rehearsing on Zoom and fine tuning the script. It was quite enchanting to see Jules bringing Mr Nicholson to life after the character had been rattling around in my brain for so long.

The UCell team could show us some of their science online – with a mini hydrogen-powered car – but we will not get the full picture until the big day. They normally participate in many live events, (and should have been in Florida for one of our rehearsals), but we were the only live event that was still on their calendar for this year.

Finding a costume for Julian turned out to be another challenge as all the theatres were closed, and consequently so were all the costumiers. Eventually a service in Bristol was identified which provides costumes to the BBC and could send it by post, so Julian had to provide his vital statistics.

September ended, and despite a variety of lockdown measures and a recent new restriction of group sizes to a maximum of six people, the event was still not cancelled. It was outdoors and thanks to Sue Heiser of FoSGG and her work on the risk assessment, it will be possible to keep everyone at an appropriate distance.

Tickets were selling and by October the live event quickly sold out its 30 tickets. But we still hadn’t nailed down the details of the online event, and while we thought we would be able to record all the interview on Zoom and the experiments on video, we were not sure how this would all come together and then be broadcast. Fortunately, Rosemary Richards called in Hannah a digital producer and Mirabel who is also at UCL and doing science outreach. There was a debate about the comparative merits of YouTube and Zoom, but the latter has the added advantage of participation and so we can have a Q&A at the end.

This put us on track and reassured us that someone who knew what they were doing would be pressing all the Zoom buttons on the day. I’ll be providing a live introduction before the interview and linking to the video, then managing the Q&A with someone from the UCL team who will handle the scientific questions.

On 7th October, we were still waiting to hear from UCell team whether they had approval from UCL to participate, and thankfully this came through and they can bring the hydrogen fuel cell stack. The costume has arrived in London, and everything is planned for next Saturday, the 17th October.

With coronavirus cases rising by the day again, and with les than a week to go, we are waiting with bated breath to hear whether there will be a “circuit-breaker” lockdown over half term or a local lockdown affecting London, and whether the live event will still go ahead.

It’s a long shot, but we re keeping our fingers crossed that the show will go on

#32,

17 and 20 October - In Conversation with William Nicholson and the UCL Ucell clean energy team at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival

August 28th, 2020share this

It is very exciting to announce that William Nicholson (1753-1815) will be making an appearance at the 2020 Bloomsbury Festival alongside the UCL hydrogen fuel cell demonstrator!

Saturday 17 October 2020,

2.30 – 3.30 pm – Live event in St George’s Gardens, London, WC1N 6BN at thewest end.

Tickets £8 (£6 concs) – Clickhere for details.

Tuesday 20 October 2020

2.30 – 3.30pm – Online event, via the Bloomsbury Festival at Home

Tickets £5 – Clickhere for details.

Termites tuck into Nicholson’s Journals in Bombay in 1859

August 9th, 2020share this

Here is an extract from the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, from Monday 28th November 1859 telling of a sad fate for Nicholson’s Journal.

“It is with much regret that the Committee have to inform the Society that the White Ants, which infect the Town Hall throughout, have found their way into the Library, and destroyed many of the books.

This was first discovered in September 1858, and since that there have been several incursions … during which 12 works or 33 volumes have been destroyed, and 12 works or 38 volumes slightly injured; fortunately those which have been destroyed have chiefly consisted of Novels, the others have been works in the classes of Classics and Chemistry; - “Nicholson’s Journal” however, has severely suffered.”

#30

Solving the C18th puzzle of scientific publishing

July 13th, 2020share this

A guest blog, by Anna Gielas, PhD

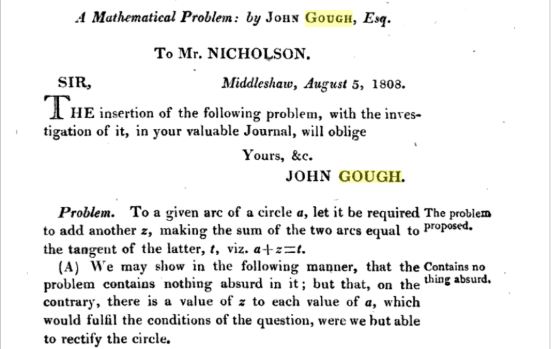

William Nicholson made Europe puzzle. Continental men of science translated and reprinted articles from his Journal on Natural Philosophy,Chemistry and the Arts on a regular basis—including the mathematical puzzles that Nicholson published in his column ‘Mathematical Correspondence’.

When Nicholson commenced his editorship in 1797, his periodical was one of numerous European journals dedicated to natural philosophy. Nicholson was continuing a trend that had existed on the continent for over a quarter of century. But at the same time, Nicholson was committing to a novel form of philosophical communication in Britain. The British periodicals dealing with philosophy and natural history were linked with learned societies. Besides the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, numerous philosophical societies in other British towns, including Manchester, Bath and Edinburgh, published their own periodicals. The London-based Linnaean Society, which had close ties to the Royal Society, also printed its transactions.

Nicholson’s editorship did not have any societal backing. He did not conduct his periodical in a group, but by himself. These circumstances made his Journal something different and novel—maybe even revolutionary. In the Preface to his first issue, Nicholson confronted the very limited circulation of society and academy-based transactions and their availability to the ‘extreme few who are so fortunate’. He made it his editorial priority to reprint philosophical observations from transactions and memoirs—to make them accessible to a wider audience.

Considering his friendship with the radical dramatist Thomas Holcroft and his collaboration with the political author William Godwin, we can think of Nicholson’s editorial priority in political terms: he wished to democratize philosophical communication. Personal experiences could have played a role here, too. Nicholson appears to have initially harbored some admiration for the Royal Society and its gentlemanly members. But he did not become a Fellow due to his social background. Whether he considered his inability to be part of the Society a social injustice is not clear. But this experience likely played a role in his decision to edit and reprint from society transactions.

There seems to be a political dimension to Nicholson’s editorship—yet the sources available today do not allow any straight-forward reading of the motives for his editorship. He did not present his editorship as a political move. Instead, he used the rhetoric of his contemporaries—the rhetoric of utility: ‘The leading character on which the selections of objects will be grounded is utility’, he wrote in his Preface. The Journal was supposed to be useful to ‘Philosophers and the Public’.

Nicholson had acquired the skills necessary for editing a periodical over many years. It seems that his organizing role in a number of societies and associations was particularly helpful to hone such abilities—for example, his membership at the Chapter Coffee House philosophical society. In mid-November 1784, Nicholson and the mineralogist William Babington were elected ‘first’ and ‘second’ secretaries of the society. During the gathering following his election, Nicholson appears to have raised 13 procedural matters for discussion and action. According to Trevor Levere and Gerard Turner, Nicholson ultimately ‘made the meetings much more effective and disciplined’.

His organizing role brought and kept him in touch with most of the Chapter Coffee House society members which enabled him to expand and affirm his own social circle among philosophers. So much so, that some of the society members would go on to contribute repeatedly to Nicholson’s Journal. As the ‘first’ secretary, Nicholson gained experience in steering a group of philosophers and experimenters towards a productive and lasting exchange—a task similar to editorship.

Nicholson was skilled in fostering and maintaining the infrastructure of philosophical exchange. His contemporaries were well aware of it and sought his support on a number of occasions. Among them was the publisher John Sewell who invited Nicholson to become a member of his Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture. Here, Nicholson and Sir Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society and Vice-President of the Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture, had one of two conflicts.

Philosophical societies in late eighteenth-century London tended to have presidents and vice-presidents, committees and hierarchies. More often than not, these hierarchies mirrored the members' actual social ranks. As an editor, outside of a society, Nicholson was free from hierarchies. He could initiate and organize philosophical exchange as he saw fit—which likely made editorship attractive to him.

For Nicholson who was almost constantly in financial difficulties, editing was also a potential source of additional income. After all, the same month the first issue of his Journal came out, Nicholson's tenth child, Charlotte, was born. But the Journal did not become a commercial success. Yet, he continued it over years, until his health deteriorated. Non-material motives seem to have outweighed his monetary needs.

His journal was an integral part of Nicholson’s later life—particularly when he no longer merely reprinted pieces from exclusive transactions. After roughly three years since the first issue appeared, his Journal began to turn into a forum of lively philosophical discourse. In the issue from August 1806, for example, he informed his contributors and readers of the ‘great accession of Original Correspondence’, which he—whether for the reason of ‘utility’ or democratizing philosophy—published in later issues rather than foregoing publication of any of them.

Outside of Britain, the Journal was read in the German-speaking lands, Russia, Netherlands, Scandinavia, France and others. Nicholson made Europe puzzle indeed. He united geographically as well as culturally and socially distant individuals, bringing European men-of-science closer together.

Further reading:

Anna Gielas: Turning tradition into an instrument of research: The editorship of William Nicholson (1753–1815),

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1600-0498.12283

#29

Summer reading: Special offer for members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association

September 30th, 2018share this

The following article was first published in the Antiquarian Booksellers' Association newsletter on 15 August 2018.

‘I used to write a page or two perhaps in half a year, and I remember laughing heartily at the celebrated experimentalist Nicholson who told me that in twenty years he had written as much as would make three hundred Octavo volumes.’

William Hazlitt, 1821

This year has seen numerous celebrations of Mary Shelley’s ‘foundational work in science fiction’, but where did Mary Shelley learn about electricity?

Historians often trace this knowledge to a copy of Humphry Davy’s Elements of Chemical Philosophy which was published in 1816 – but many years before this, the child Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin had access to scientific instruments at 10 Soho Square with her playmates – the five daughters of William Nicholson (1753-1815).

The scientist and publisher William Nicholson was one of her father’s closest friends. In his diary, William Godwin records more than 500 meetings with Nicholson and his family between November 1788 and February 1810. Aside from their mutual friend the dramatist Thomas Holcroft (1,435 mentions) and direct family members, only a handful of other acquaintances are mentioned more frequently in Godwin’s diary.

Nicholson had opened a Scientific and Classical School at his home in Soho Square in 1800. It was here in the Spring that, with Anthony Carlisle, he famously decomposed water into hydrogen and oxygen using the process now called electrolysis.

Electrical experiments had long been an interest of Nicholson who had two papers on the subject read to the Royal Society by Sir Joseph Banks in 1788 and 1789.

In those days, science - or natural philosophy as it was called - was also a leisure activity. Scientific instruments were the latest toys for the affluent and experiments provided entertainment. One after-dinner game was The Electric Kiss: where young men would attempt to kiss a young lady who had been charged with a high level of static electricity. Sadly, the kisses were rarely obtained as, on approaching the young lady, the men would be jolted away by an electric shock.

In a house full of several children, and a dozen energetic students, Mary witnessed and is likely to have participated in experiments and pranks with the air pump or Nicholson’s revolving doubler – his invention of 1788 with which you could create a continuous electrical charge.

Despite his circle of literary friends, Nicholson is better known among historians of science for A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts which ran between 1797 and 1813 and was the first monthly scientific journal in Britain. It revolutionised the speed at which scientific information could spread - in the same way that social media has done more recently - and the Godwin family no doubt received copies.

Full sets of Nicholson’s Journal, as it was commonly known, are rare. Certain editions are particularly sought after, such as those which include George Cayley’s three papers on the invention of the aeroplane.

But Nicholson’s first success as an author was fifteen years previously with his Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782. This was the same year that he wrote the prelude to Holcroft’s play Duplicity.

Nicholson quickly abandoned writing for the theatre, but he never abandoned his literary friends with their anti-establishment views, and his body of work is more extensive than the voluminous scientific translations and chemical dictionaries for which he is best known – some of which change hands for thousands of pounds.

Other works included a six-day walking tour of London, a book on navigation – based on Nicholson’s experiences as a young man with the East India Company – and translations of the exotic biographies of the Indian Sultan Hyder Ali Khan and the Hungarianadventurer Count Maurice de Benyowsky. Nicholson also contributed short biographies for John Aikin’s General Biography series; he launched The General Review which ran for just six months in 1806; and heproduced a six-part encyclopedia.

Before Nicholson came to London, he had spent a period working for the potter Josiah Wedgwood in Amsterdam. Wedgwood held young Nicholson in high regard, commenting in 1777 that ‘I have not the least doubt of Mr Nicholson's integrity and honour’. Then in 1785, when Wedgwood was Chairman of the recently established General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain, he appointed Nicholson as secretary. In this role, Nicholson produced several papers on commercial issues including on the proposed IrishTreaty and on laws relating to the production and export of wool.

Towards the end of his life, Nicholson put his technical knowledge to work as a patent agent and later as a civil engineer, consulting on water supply projects in West London and Portsmouth. The latter project faced stiff competition from another local water company and, in 1810, Nicholson published A Letter to the Incorporated Company of Proprietors of the Portsea-Island Water-Works.

As William Hazlitt indicated, in the opening quotation, Nicholson’s works were extensive. His activities were varied and there is much in his writings that will be of interest to historians of literature, commerce and inventions, as well as to historians of science and the Enlightenment.

A full list of Nicholson’s publications can be found in The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son, which was first published by Peter Owen Publishers earlier this year (£13.99). The original manuscript, written 150 years ago in 1868, is held at the Bodleian Library.

Free postage and packing is offered to members of the ABA when purchasing direct from www.PeterOwen.com. Simply use the Coupon code ‘1753-1815’ in the shopping cart before proceeding to checkout.

#25

The Enlightenment Flyfishers (first published in Flyfishers' Journal)

July 12th, 2018share this

'Angling - Preparing for Sport': published in 'British Field Sports' in 1831, this copper-engraved print depicts the kind of fishing tackle and clothing which would have been familiar to Sir Humphry Davy's literary characters Halieus, Ornither, Poietes and Physicus.

Salmononia: or Days of Fly Fishing, first published in 1809 by the Cornish chemist and inventor Humphry Davy (1778-1829), is one of the most collectable of angling books from the early nineteenth century. It was dedicated to the Irish physician and mineralogist, William Babington, a longstanding friend of Davy and a fellow founder of the Geological Society of London in 1807.

The book, written while Davy was ill, takes the form of a series of discussions between four imaginary characters: Halieus, the accomplished fly fisher; Ornither, a county gentleman who has done a little fishing; Poietes, a fly-fishing nature-lover; and Physicus a natural philosopher who has never fished.

John Davy, in his Memoirs of the Life of Humphry Davy, paints a wonderful picture of his brother on the river:

"I am sorry I have not a portrait of him in his best days in his angler’s attire. It was not unoriginal, and considerably picturesque – a white, low-crowned hat with a broad brim; its under surface green, as a protection from the sun, garnished, after a few hours’ fishing, with various flies of which trial had been made, as was usually the case; a jacket either grey or green, single-breasted, furnished with numerous large and small pockets for holding his angling gear; high boots, water-proof, for wading, or more commonly laced shoes; and breeches and gaiters, with caps to the knees made of old hat, for the purpose of defence in kneeling by the river side, when he wished to approach near without being seen by the fish; such was his attire, with rod in hand, and pannier on back, if not followed by a servant, as he commonly was, carrying the latter and a landing net."

Humphry Davy admits that Salmononia was inspired by ‘recollections of real conversations with friends’ and John’s memoir revealed that Halieus was inspired by William Babington. But whose conversations inspired the other characters?

Two friends of both Davy and Babington that must be strong contenders are William Nicholson (1753-1815) and Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840). They are best known for their decomposition of water into hydrogen and oxygen by electrolysis, achieved in 1800 with a copy of Alessandro Volta’s recently invented pile – a discovery which so excited Davy that he wrote that: ‘An immense field of investigation seems opened by this discovery: may it be pursued so as to acquaint us with some of the laws of life!’

Davy met Nicholson when he arrived in London, having already corresponded and sent his first scientific papers to him in 1799 for publication in A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first monthly scientific publication in Britain, running between April 1797 and December 1813. Over the course of its life, Nicholson’s Journal included some twenty articles on fish (but not specifically fly fishing). The most important was the editor’s own in the article on the torpedo fish in 1797, which speculated about the source of the electric charge within the pelicules of the torpedo, and which inspired Volta to try the various combinations of discs (an important hint) resulting in the development of his battery pile. When Davy was appointed as Director of the Royal Institution, aCommittee for Chemical Investigation and Analysis was established, on which Nicholson was invited to participate.

Nicholson had known Babington since 1784 when they were joint secretaries of a philosophical coffee house society established by Richard Kirwan, another Irish chemist and geologist. He also knew Carlisle, then at Westminster hospital, through his close friend the radical author William Godwin whose wife Mary Wollstonecraft was attended by the surgeon before she died in 1797.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an account of Davy, Babington, Carlisle and Nicholson fishing together, but it is a scene that we might easily imagine.

Nicholson, who was a prolific publisher, in his 1809 British Encyclopedia, or Dictionary of Arts and Sciencesdescribes fly fishing as ‘an art of so much nicety, that to give any just idea of it, we must devote an article to it.’ Sadly, he does not write about fly-fishing as eloquently as he does about chemistry, simply describing a number of flies and his only advice on how to fish is ‘keep as far from the water’s edge as may be, and fish down the stream with the sun at your back, the line must not touch the water.’

But, in a memoir of The Life of William Nicholson, the manuscript of which has finally been published 150 years after it was written, there is a charming account by Nicholson’s son of fishing trips with Carlisle in around 1803:

"Carlisle was at that time about thirty years of age, good looking and active …

Having passed his early days at Durham and in Yorkshire, Carlisle was fond of the country and country sports. We had many a day’s fishing at Carshalton, where his intimacy with the Reynolds and Shipleys procured him the use of part of the stream where the public were excluded. He was a skilful fly fisher and during the day I generally carried the pannier and landing net, but towards night when the mills stopped, and the water ran over a bye-wash, I with my bag of worms and rod managed to hook some fish as big as were taken during the day.

We also had fishing grounds at a place in Hertford called Chenis which was rented as I understood by Carlisle and a fellow sportsman called Mainwaring. These two gentlemen and myself as a third in a post-chaise used to start at 6.00 o’clock am, breakfast at Ware or Hoddesdon and forward to the fishing, which was fine for a boy of fourteen. And then Mr Mainwaring always took a fowling piece with him and occasionally shot a bird which was worth all the fish, rods and lines and all.

Chenis was a remarkably quiet rural place and the little inn we slept at was situated in a settlement of some half dozen cottages and houses, but what its name was I do not know. On one occasion when our companion was called away Carlisle and I remained there for a day or two. We were very successful in our fishing and were about to depart when it turned out there was a county election going forward and there was no conveyance to be had for love or money. Carlisle was wanted at home and we had no choice but to start on foot, so away we went after breakfast with a boy to show us a footpath way through fields to Rickmansworth where we hoped to get some conveyance to London.

Carlisle had the best share of the luggage and the boy and I the remainder. The country we travelled was beautifully undulated and of a dry sandy soil. It was very hot and I suspect I was the first to feel fatigue. After a long trudge we stopped at a gate leading into a sandy lane and looking back at the hillside I was amazed at the display of poppies in full bloom, the whole field was a mass of crimson, a new sight to me.

I was very thirsty and tired and have often thought of that field and Burns’ immortal lines:

Pleasures are like poppies spread;

You seize the flower, its bloom is shed;

or like the snow fall on the river.

a moment white then melts forever.[1]

But time, like a pitiless master, cried onward and we had to trudge again. At last our guide left us on the dusty high road to Rickmansworth, where in time we arrived. Here we got some refreshment and awaited til a return post-chaise conveyed us to London. We had walked nearly 30 miles and it was my first walking adventure of any magnitude."

The story was written when young Nicholson was eighty, and his geography seems a bit muddled – I have been unable to locate a place called Chenis, in Hertford – but records exist for one in Buckinghamshire in the 1770s. Could he mean the river Chess if he was near Ware and Hoddesdon? The Chess also passes near a village called Chenies just a few miles from Rickmansworth. (If any readers of the Flyfishers’ Journal can help, I would be very interested to hear from them.)

Carlisle went on to enjoy a stellar medical career, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1804, where he became Professor of Anatomy 1808 to 1824.

In 1809, he published an account of some experiments into how fish swam, by cutting various fins off seven fish each of dace (cyprinus leusiscus), roach (cyprinus rutilus), gudgeon (cyprinus gobio) and minnow (cyprinus phoxinus). He recorded how, on removal of the pectoral fin [2] its progressive motion was not at all impeded, but it was difficult for the fish to ascend; on removing the abdominal fin as well, the fish could not ascend; on removing the single fins, ‘produced an evident tendency to turn around, and the pectoral fins were kept constantly extended to obviate that motion; … and so on, until all fins had been removed from the seventh fish which cruelly ‘remained almost without motion’.

Carlisle was appointed Surgeon Extraordinary in 1820 to King George IV and was knighted in 1821. He died in 1840, never losing his love of fishing.

"Sir Anthony Carlisle had been called into the Prince Regent mainly to consult as to what wine he should drink. Having ascertained that brown sherry was the favourite of the day, he recommended it and gave great satisfaction.

Carlisle wrote to me, while I was engaged in a survey in Yorkshire, to find him a handy honest unsophisticated lad as a servant. I did my best and sent him one. The lad turned out a stupid dog, but when I visited London a short time afterwards and dined with Carlisle this boy waited and amused me by incessantly answering Carlisle ‘Yes Sir Anthony, … no Sir Anthony’ and ‘Sir Anthony’ at the beginning, middle and end of every sentence. All this passed as a matter of course and reminded me how calmly we bear our dignities when they fall upon us.

Carlisle was a true fisherman and a great admirer of honest Izaak Walton and used to quote from that delightful book The Compleat Angler, so that when any food or wine was better than common he said ‘it was only fit for anglers or very honest men’; and then he had another joke when we got thoroughly wet on our fishing excursions, saying ‘it was a discovery, how to wash your feet without taking off your stockings’."

#24

[1] From Robert Burns, ‘Tam o’ Shanter’, Edinburgh Magazine, Mar 1791.

[2] All these articles can be found by searching the index.

In print at last after 150 years: 'The Life of William Nicholson, by his Son'

February 24th, 2018share this

I was extremely fortunate in having been signed by one of the leading independent publishers - Peter Owen Publishing. This was the first publisher that Iapproached (so very fortunate indeed) and is surely testament to the importance of Mr Nicholson, rather than my own humble credentials.

As the main biography is taking much longer than anticipated (see below), we decided to publish The Life of William Nicholson by his Son as a prelude - exactly 150 years after it was written in 1868. This rare manuscript has been held by the Bodleian Library since 1978.

In addition to the edited text of The Life of William Nicholson by his Son, the book also includes:

- a timeline of Nicholson's life, work and inventions;

- details of Nicholson's published works;

- Nicholson's patents and inventions;

- Nicholson's list of members of the coffee house philosophical society of the 1780s (not as complete as in Discussing Chemistry and Steam by Levere and Turner …, but indicative of Nicholson's associates at the time); and

- committee Members of the Society for Naval Architecture of 1791.

Design agency Exesios have done a super job of the cover, and there is a special treat on the inside with:

- a map of all Nicholson's known homes on (Drew's map of 1785); and

- the drawings from the 1790 cylindrical printing patent.

I'm delighted that Professor Frank James of UCL and the Royal Institution has written an afterword which focuses on Nicholson's scientific contributions. Considering his literary associates, Professor James also suggests why Nicholson was never made a member of the Royal Society, despite his many achievements.

The modern biography of William Nicholson (1753-1815)

With 110,000 words under my belt, I was beginning to think that the end was in sight on the modern biography - until I met up with Hugh Torrens, Emeritus Professor of History of Science and Technology at University of Keele, to chat about some of the civil engineering issues.

Our first meeting resulted in a very exciting list of 29 items of further research which will keep me busy researching and writing for several months.

Meanwhile, you can keep up to date with news and developments here on the blog.

#22

It's complicated! Nicholson's relationship with Sir Joseph Banks

February 10th, 2018share this

This weekend the Sir Joseph Banks Society is celebrating the 275th birthday of the larger-than-life Georgian, who dominated the Royal Society for decades.

William Nicholson (1753-1815) is best known to Enlightenment historians as the founder of A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts – the first commercial monthly scientific journal in Britain. Taking a wide variety of articles from all levels of society, Nicholsons Journal, democratised access to technological developments, encouraged debate and accelerated the spread of scientific know-how. However, it was a thorn in the side of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, and Sir Joseph Banks is reported to have blocked Nicholson’s membership to the Royal Society on the basis that he wanted ‘no journalists’ or ‘sailor boys’ – the latter a reference to Nicholson’s early career with the East India Company and a contretemps at the short-lived Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture.

Despite this, they enjoyed a cordial relationship over at least 20 years. Nicholson was first engaged by Banks to help produce the paper Observations on a Bill, for Explaining, Amending, and Reducing into One Act, the several laws now in being for preventing the Exportation of Live Sheep, Wool, and other Commodities, 1787.

Shortly after this, Banks accepted the first of three papers from Nicholson for the Royal Society – one on a proposed design for a compact scale rule to replace the cumbersome Gunther’s rule; one in 1788 regarding Nicholson’s invention of the revolving doubler (a device to generate electricity) and a third paper on electricity was read in 1789.

In 1799, Nicholson moved to Number 10 Soho Square where he established a scientific school and hosted a series of scientific lectures. He was a regular participant at Banks’s Sunday Conversazione and the Thursday breakfast held in the Banks library.

In 1802, a disagreement arose when Nicholson wrote to Banks asking permission to republish papers from the Royal Society, as was happening in foreign journals – he argued that it was unfair that ‘journalists within the Realm should be put in a less favoured situation than foreign philosophers’.

Working relations resumed, and in 1806, on behalf of the Board of Longitude, Banks invited Nicholson to comment on designs of the timekeepers constructed by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw hoping to reveal the secrets of their designs to the wider watch-making community and thereby stimulate similar developments.

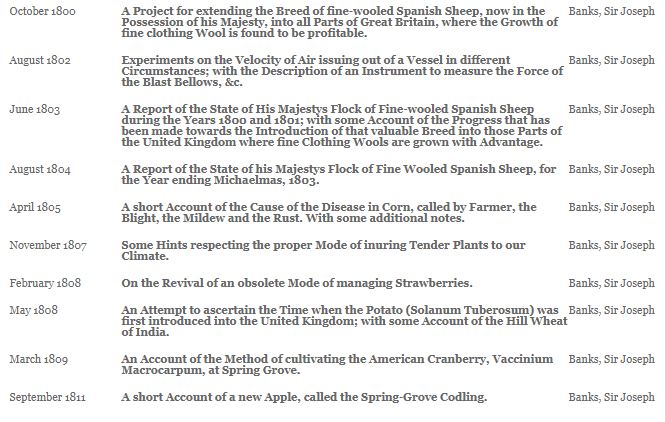

Between 1800 and 1812, 14 articles by Banks were published in Nicholson’s Journal – so in the end, even Sir Joseph recognized the benefits of speedier dissemination of scientific information.

These articles can ve accessed via: http://www.nicholsonsjournal.co.uk/nicholsons-journal-index.html

#21

The Navigator’s Assistant, published by John Sewell, Longman and Cadell

October 15th, 2017share this

Checking a few of the links on our list of Nicholson’s publications, I was delighted to find that there is now a copy of The Navigator’s Assistant available to read on Google Books.

The previous link (via the Hathitrust) attributed the book incorrectly to William Nicholson ‘master attendant of Chatham dockyard’. Unfortunately, quite a few other online links make the same error (including one on Worldcat – where I was surprised that I could not find a facility to report the error).

Published in 1784 in two volumes for 6 shillings, more than ten years after he had returned from his second voyage to China, this was Nicholson’s second publication in his own name. It followed on from the success of his An Introduction to Natural Philosophy in 1782.

Despite the success of his first book, Joseph Johnson was not interested in a work on navigation, and Nicholson eventually persuaded three publishers to spread the risk and work with him. These were Thomas Longman of Paternoster Row (1730-1797), Thomas Cadell of The Strand (1742-1802) and John Sewell of Cornhill (c1733-1802).

Sewell became a good friend of Nicholson, and was an interesting character. His shop in Cornhill was described in his obituary as “the well-known resort of the first mercantile characters in the city, particularly those trading to the East Indies. “ “He possessed, besides his professional judgement of books, a tolerable knowledge of mechanicks, particularly of ship-building … and was a most zealous promoter of a Society for the Improvement of Naval Architecture,” - of which he persuaded Nicholson to become a member.

Two other historic nuggets - with no relation to Nicholson, but rather interesting - caught my eye in his obituary:

Businesses in Cornhill had suffered from a number of fires, and so Sewell came up with the idea of building a water tank beneath the coach-pavement which was kept full and was a ‘perpetual and ready resource in cases of fires happening in the vicinity.’

In 1797 mutinies were threatened by sailors of the Royal Navy – a time when Britain was at war with France – “the kingdom was alarmed and confounded” and John Sewell drew up plans for a Marine Voluntary Association “for manning in person the Channel Fleet”. Fortunately, the sailors came to their senses and the volunteers were not required.

Returning to The Navigator’s Assistant, this was not a great success. The Monthly Review described it as “undoubtedly the work of a person who is possessed of ingenuity enough to leave the beaten path” but goes on to criticise a number of technical errors.

The Gentleman’s Magazine kindly described it as “too refined and laboured for the class of persons to whom it was addressed: and therefore it is not much to be wondered at that this Assistant was neglected”.

#15

Book review: The Enlightened Mr Parkinson

July 28th, 2017share this

As we near publication of the Life of William Nicholson by his son, I find myself scanning the shelves of every bookshop to see whether much, if any, space is given to Georgian biographies. I was delighted to come across this biography in prime position on the New Releases shelf: THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon by Cherry Lewis.

Parkinson identified a specific type of shaking palsy and it is this mental health condition for which his name is recognised today, but the biography tells a broader story of his work in general medical practice, his involvement in social and political reform, and his interest in fossils and geology. He was one of the founders of the Geological Society in 1807.

I particularly enjoyed the way that the author has explained the background at a time of tumultuous and constant change occasioned by wars, political upheaval, societal advances, medical and scientific discoveries. This is done in a very accessible way which ensures that the book will be just as enjoyable for a reader who is not intimate with that period of his life, between 1755 and 1824.

Parkinson’s life coincided pretty well with William Nicholson (1753-1815). They would certainly have met at the Geological Society, which Nicholson joined on the suggestion of their mutual friend Anthony Carlisle, if not in the mid-1790s when Parkinson was a member of the London Corresponding Society with Nicholson’s good friend Thomas Holcroft.

Parkinson submitted four papers to Nicholson’s Journal:

October 1807 - Nondescript Encrinus, in Mr. Donovans Museum.

March 1809 - On the Existence of Animal Matter in Mineral Substances.

May 1809 - On the Dissimilarity between the Creatures of the present and former World, and on the Fossil Alcyonia.

January and February 1812 - Observations on some of the Strata in the Neighbourhood of London, and on the Fossil remains contained in them.

THE ENLIGHTENED MR. PARKINSON – The pioneering life of a forgotten English surgeon

By Cherry Lewis, published by ICON

http://www.iconbooks.com/ib-title/the-enlightened-mr-parkinson/

#10

Richard Kirwan’s Philosophical Society (1780-1787)

March 20th, 2017share this

In December 1780 in the Chapter Coffee House near St Paul's Cathedral, several men led by the Irish chemist Richard Kirwan decided to meet fortnightly to discuss ‘Natural Philosophy, in its most extensive signification’.

The membership of the group grew steadily, and meetings took place in a variety of locations including the Baptist’s Head Coffee House. William Nicholson joined in 1783 and was elected joint secretary with William Babington in 1784.

Nicholson’s copy of the minutes of the society, until 1787 when it folded, are in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science and it was wonderful to be able to inspect them recently.

Compared to other philosophical societies of that time, especially the Lunar Society which had been meeting in the Midlands since 1765, this group seems little known – partly because it never had any name.

In 1785 it was agreed that the group would have no formal name when Kirwan ‘affirmed that the society not being desirous of that kind of distinction which arises from name or title were so far from giving any sanction or authority to the names used by their secretaries that the original determination in this respect was that the society should not have a name.

Fortunately the minutes do include a most interesting list of 35 members (the total number of members over the life of the society was 55).

Mr Alex Aubert (1730-1805), Austin Friars, 26

MrWilliam Babbington(1756-1833)

MrAndrewBlackhall (?-?), Thavies Inn, Holborn

DrWilliamCleghorn(1754-1783), Haymarket, 11

DrJohnCooke(1756-1838)

DrAdairCrawford(1748-1795), Lambs Conduit Street, 48.

MrJean-Hyacinthde Magellan(1722-1790), Nevilles Court, 12

MajorValentineGardiner(1775-1803)

DrWilliamHamilton(1758-1807)

MrJamesHorsfall(-d1785), Inner Temple.

DrJohnHunter(c1754-1809), Leicester Square

DrCharlesHutton(1737-1823)

MrWilliamJones(1746-1794), Inner Temple

DrWilliamKeir(1752-1783), Adelphi

MrRichardKirwan(1735-1812), Newman Street, 11

DrWilliamLister(1756-1830)

MrPatrickMiller(1731-1815), Sackville Street, 17

MrEdwardNairne(1726-1806), Cornhill, 20

MrWilliam Nicholson(1753-1815)

DrGeorgePearson(1751-1828)

DrThomasPercival(1740-1804)

DrCharles William Quin(1755-1818), Harmarket, 11

DrJohnSims(1749-1831), Paternoster Row, 11

MrBenjaminVaughan(1751-1835), Mincing lane

MrAdamWalker(c1731-1821), George Street, Hannover Square

DrWilliam CharlesWells(1757-1817), Salisbury Court

MrJohnWhitehurst(1713-1788), Bolt Court, 4

DrJohnWatkinson(1742-1783), Crutched Friars, 22

Honorary members

DrMatthewBoulton(1728-1809), Birmingham

MrRichardBright(1754-1840), Bristol

MrJamesKeir(1735-1820), Birmingham

DrRichardPrice(1723-1791), Newington Green

Rev'd DrJosephPriestley(1733-1804), Birmingham

MrJamesWatt(1736-1819), Birmingham

MrJosiahWedgwood(1730-1795), Etruria

Further information

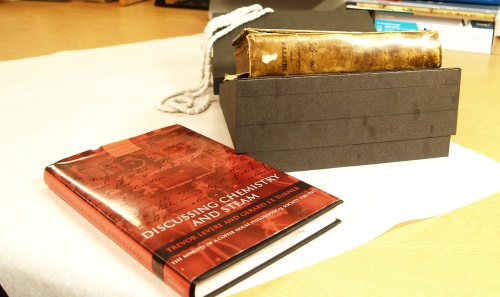

The entire set of minutes, as well as descriptions of all the members of the society, are set out in Discussing Chemistry and Steam: The Minutes of a Coffee House Philosophical Society 1780-1787, by Trevor H. Levere and Gerard L'E Turner.

Available from Oxford University Press

#5

21stC readers of Nicholson's Journal

Can you shed light on

Mr Nicholson’s life?

Propose a guest blog

The Life of William Nicholson, 1753–1815

A Memoir of Enlightenment, Commerce, Politics, Arts and Science

Edited by Sue Durrell and with an afterword by Professor Frank James

£13.99

Order from Peter Owen Publishers

Order